By Mark CunninghamPublished December 1995

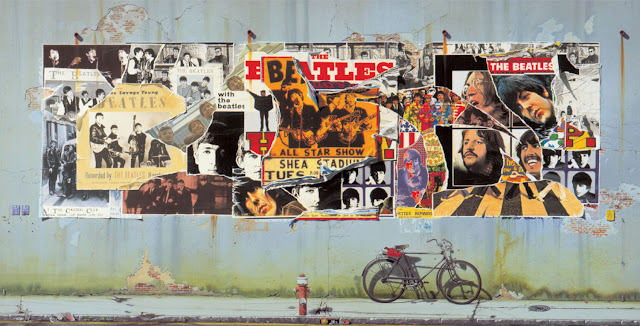

After years of rumours and myth, the fruits of The Beatles' reunion for small screen and recording projects can now be experienced by mere mortals. For the past 18 months, Mark Cunningham has been keeping his ear to the ground, and can now reveal the fascinating details surrounding the Fab Four's 'Second Coming'...

Apple Corps Ltd in Knightsbridge was under telephone siege the day I called in on The Beatles' press officer, Derek Taylor. "It's a new strain of Beatlemania," he laughed. "See that phone?" he said, pointing at his twinkling extension display. "It should have stopped ringing in 1970, but I've never been so busy." It is a phenomenon that he has expected and prepared for at a time when a television series, several videos, a book and three double CD sets, collectively known as the Anthology, are about to spread a harvest around a world starved of The Beatles for the last 25 years.

The Continuing Story...

The story behind the Anthology began in 1989, when the three surviving Beatles, together with Yoko Ono and their Apple aides, initiated a series of business meetings where plans for the definitive television history of the band were drawn up. The message was clear: it was to be the story of The Beatles, as told by The Beatles.

One thing was certain: it wasn't as though the story would have no audience. The worldwide adulation for Liverpool's most famous sons has not flagged over the quarter of a century which has passed since their acrimonious break‑up. Last year's release of the Live At The BBC collection of rare radio broadcast performances (see SOS March 1995) saw record buyers queuing overnight on both sides of the Atlantic to be among the first to own copies. A worthy release in itself — but it only served to whet our appetite while we waited for the main event.

To coincide with the imminent six‑part screening of the Anthology TV documentary, EMI Records is to release three double CD sets of ultra‑rare Beatles material, gleaned from the Fort Knox‑like vaults of Abbey Road Studios, private collections and other sources. To compound the excitement, the collection will feature two new Beatles recordings, featuring contemporary vocal and instrumental backing by Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr, added to unfinished demos by the late John Lennon. Eagerly awaited by the world like no other record in history, and guarded with a veil of secrecy that would make MI5 proud, the first of these two tracks, 'Free As A Bird', is expected to be this year's Christmas Number One single — a strange echo of the group's regular seasonal success in days gone by.

By releasing an estimated total of around 150 previously unreleased Beatles tracks, EMI will do much to devalue the hitherto healthy business of Beatles bootlegging, an area that has made large profits for industry rogues. Although tracks which have appeared in bootleg form will resurface in a far superior guise on the Anthology releases, there are many so rare that they have never been heard outside of The Beatles' immediate circle.

I met and discussed the Anthology project with veteran Beatles producer George Martin and Geoff Emerick, his engineer since 1966, during the week that EMI took delivery of the completed masters for the first volume of the Anthology. This release covers the years 1958 to 1964 — from the days of pre‑Beatles band The Quarrymen up to the album Beatles For Sale. Released on November 21st, the album contains 60 tracks, forming a veritable treasure trove of 'lost' songs, home‑made demos, alternate takes and in‑concert performances.

Get Back

Martin and Emerick's work on the Anthology CDs began immediately after the completion of the Live At The BBC album. But plans had already been in place for some considerable time."There had been talk of this between The Beatles and Neil Aspinall at Apple for about five years before we actually got to work on it," says Martin. "The project was originally called The Long And Winding Road, and it certainly has been one, but the actual shape of what it has become was not truly defined. I was asked to produce it, and I presented both Apple and EMI with different ideas of what could be done. That's when we started in earnest, although this has been almost a continuation of what we did with the BBC tapes.

"Over the course of the project, I have listened to everything we ever recorded together. Every take of every song, and every track of every take. So in that respect, I have relived my life all over again! I have also listened to innumerable broadcasts, live performances, bootlegs, television shows and interviews: virtually everything that was ever committed to tape and labelled 'The Beatles'. I've heard about 600 separate items in all, but I would imagine there are still a few things out there that even I don't know about. I didn't start any serious listening until the early part of this year, when I got Paul, George and Ringo to come in occasionally and listen with me. Of course, they couldn't sit through all of the sessions, so I would tend to have them come in about once a week."

Plundering The Archives

While most of the Anthology tracks originate from Abbey Road Studios, others have been located with the assistance of people such as Beatles historian Mark Lewisohn, Stefan Olander and TV companies including Granada. Of the most rare to feature on the first volume of the Anthology is the 1958 coupling of the McCartney/Harrison‑composed, doo‑wop styled 'In Spite Of All The Danger' and a cover of Buddy Holly and The Crickets' 'That'll Be The Day'. These were the first recordings made by Lennon, McCartney, Harrison, drummer Colin Hanton and pianist John 'Duff' Lowe (then known collectively as The Quarrymen) in a back room studio at 53 Kensington, Liverpool.

Martin comments: "That was when they were very young — George was only 15, Paul was 16 and John nearly 18. They all clubbed together to pay for the recording session and the result was a double‑sided shellac disc which they each kept hold of for about a month at a time, but one of the two who eventually left the group forgot to pass it on. Paul later bought the disc back from him. I don't know what he paid for it, but it must have been for considerably more than his share of the studio hire cost! So those two tracks effectively come from Paul's private collection".

Fixing A Hole

The two songs required a degree of audio cleansing before they made it on to the Anthology, thanks to Peter Mew of Abbey Road and the Sonic Solutions audio enhancement technology with which he has become an expert over the past six years. "I'm not an engineer," comments George Martin. "I just tell Peter what I like, and if I don't like something I'll throw it back at him, and tell him that the EQ or some audio 'pasting' is wrong, or whatever. I wouldn't dream of standing over his shoulder."

Martin insists that the 1958 recordings are not the worst examples of audio quality he had to work with, and refers to an address he gave at last year's San Francisco AES Convention, where he made an appeal to delegates regarding the renovation of old recordings. "All we can do at the moment is to take out noise and enhance what is there, but we cannot restore what is missing. Now in video, you can improve visual quality, because the computer will work out the nature of the missing information and restore it. Why can't we have that in sound? Why can't we have something that tells us which frequencies are missing and then restores them? So far, nothing can be done, so we have had to deal with the technology we have."

Abbey Road

In complete contrast to other discovered gems, the material guarded by Abbey Road Studios was largely in excellent condition because, as Martin says, "they really know how to look after their tapes. Those that they have kept, that is, because they destroyed an awful lot of the early ones. In fact, there are very few tapes left from the early 1962‑63 sessions. A lot of the material that has come to light from that period has been in the form of lacquers and acetate discs. Occasionally, some quarter‑inch tapes have emerged, but no masters as such. Of course, in the very early days, the masters were only mono on twin track anyway.

"I didn't have any say over the stuff that was destroyed, because that was EMI's decision. In 1962, no one would have given tuppence for the future of The Beatles. I was practically laughed out of court when I presented their first recording to the EMI sales staff, because they thought it was another one of my jokes. So at that time, it was hardly surprising that they decided to make room in their library for what they considered to be more important recordings. But once we got into four‑track, they did keep the tapes, and the importance of maintaining a complete archive of their session tapes grew with the group's stature."

Only Some Northern Songs

A big find, lurking anonymously for years inside an Abbey Road closet, was George Harrison's demo of his unissued song, 'You Know What To Do', recorded in June 1964. Thanks to Martin's wife Judy, examples of The Beatles with drummer Pete Best are also included. Martin: "We only managed to get hold of two tracks from the very first session the boys did with me in June 1962, and I happened to have one of them. My wife found it and it transpired that no one else had it. That was 'Love Me Do', the other being 'Besame Mucho', both with Pete Best on drums. Some of the other rare recordings include songs which were done at Paul's house in Forthlin Road, Liverpool when he was about 16. The quality is rather grotty, but they are very interesting, historically, because of the presence of Stuart Sutcliffe.

"There are things which I thought had gone forever, such as an early version of 'Please Please Me' which we recorded in September 1962 at the end of the 'How Do You Do It?' session. This was recorded in the last half hour of the session, and it doesn't have the harmonica on it, but it's very interesting, with a totally different drum sound.

"After 30 years or more, you are bound to forget some detail. Occasionally I'd stumble over something and say, 'Gosh, that really was so good.' Then one wonders why we went on to change it! To me, some of the first takes of many of the songs are gems. They have rough edges which are obviously smoothed out over the course of later takes, but there's a quality and style, particularly about the voices, which is absolutely captivating. It is those examples which make the Anthology project thoroughly worthwhile, and it will give a lot of people immense pleasure to hear them at last, I'm sure."

For Geoff Emerick, the experience of hearing raw session tapes from the Sgt. Pepper period was all too much at times. "They haven't been heard in these conditions since they were originally recorded and mixed," he says. "The little bits of chat and announcements in between the songs bring back memories so vivid that it only seems like a couple of years ago. Songs like 'A Day In The Life' and 'Penny Lane' are historical monuments, and every little nuance and guitar note is priceless."

Geoff Emerick: "Songs like 'A Day In The Life' and 'Penny Lane' are historical monuments, and every little nuance and guitar note is priceless."

With around 600 individual recordings at their disposal, Martin and Emerick, in consultation with the three surviving Beatles, set their own criteria for which tracks would qualify for release. Martin explains: "In this series of CDs, I am telling the life story of The Beatles, and therefore almost every song should be included. But so much of The Beatles' material has been already been issued, and there's no point in giving people what they already have. So unless a track was really different or historically interesting, I wouldn't include it. If it was bad technically, then it had to be awfully good from other points of view to make it into the collection, because at all times I was trying to achieve the best possible quality. Among the earlier recordings there are a couple of tracks which I thought were not really up to scratch, technically. But they are all that exist from that particular period, and because it's history they deserve the exposure. The live recordings we listened to from the Cavern and Hamburg were too poor to consider".

Retro Demands

Archived Beatles tapes are never allowed outside the Abbey Road building. As a result, all the listening and subsequent mixing sessions have been held at the studio's Penthouse Suite, using a Studer A80 multitrack for playback. For previous internal playback reasons, EMI's Allan Rouse had made copies of all The Beatles' original multitrack masters on a digital machine to prevent the masters from being handled. But it was when listening to these transfers that alarm bells began to ring in the ears of Martin and Emerick.

"I was listening to Allan's copies one day before we started mixing, and I asked him if he had EQ'd them, because the top end sounds, particularly the cymbals, appeared modern and artificial," says Emerick. "What I was noticing was the quality of the digital transfer and the sound of the digital machine. But we wanted to achieve a result that was as near to the original formula as possible, so we have been using Fairchild 660 limiters and old EMI EQ boxes. In fact, the only truly modern things in the control room are the Meyer HD1 monitors. We have mixed everything down on half‑inch on a Studer A80 at 30ips."

The normally beneficial modern technology that is plentiful at Abbey Road posed a dilemma for George Martin: "I told Rupert Perry [head of EMI Records] that if I was going to remix a recording made in the 1960s on four or even eight tracks, there would be no point in processing it in a modern manner, and that I would need a console from approximately that period. The recordings themselves weren't designed for modern techniques, and we would be presenting something alien if we did that. I was told that we had to use Abbey Road, but the problem with Abbey Road is that there are SSL desks all over the place — and SSL is not the right medium for these old recordings. At a pinch, a Neve desk would be kinder, but even that's not right. What I really wanted was an old valve desk, although I knew that it would be causing more trouble than it was worth, because if we found something suitable it would inevitably be unreliable. To our great fortune, however, we discovered that Jeff Jarratt [an ex‑Abbey Road engineer who worked with The Beatles and later produced the successful Classic Rock album series] had this early 1970s console, which was among the first transistorised models to arrive at Abbey Road. It's jolly good, and there is no question that it does affect the sound. So we took over the Penthouse Suite, which normally has a Capricorn desk, and replaced it with Jeff's for these mixing sessions."

Jarratt's console is an EMI TG‑series TG12345 Mark II 24/8/2 mixer, designed and built by EMI, and issued for use in one of its mobile recording units in January 1970, the month of the Beatles' last recording session. When the console went up for sale in 1987, Jarratt purchased it for installation in his own Hertfordshire home studio. When George Martin's pleas for authenticity reached the ears of Abbey Road's management, they called Jarratt in May to enquire about the availability of the console. Jarratt says: "The engineers at Abbey Road have always taken great care of the console for me and it was well‑known among the staff that I had bought it from the studio in '87."

On 13 May 1995, Geoff Emerick visited Jarratt to inspect the desk and promptly deemed it suitable. On the following Thursday, 18 May, the console was whisked away by Abbey Road staff and installed for a string of mixing sessions which began in earnest on 22 May in the Penthouse Suite. "It may be my console," says Jarratt, "but I've been kept as much in the dark about the project as everyone else. They initially asked to hire it for three months, but I can't see myself having it back just yet."

Finding a suitable console was one obstacle out of the way, but with many tracks requiring effects, George Martin faced yet another hurdle. "In the spirit of the exercise, I couldn't justify using modern effects processors like digital reverb, or even echo plates, which didn't exist in the '60s. The only way we could achieve echo was by using either a chamber or tape delay, or a combination of both. So I told EMI that it was important I worked in exactly the same way on these remixes. Unfortunately, neither of the two echo chambers that we used at Abbey Road were available — one has an enormous amount of electrical plant in it, emitting terrible humming noises. But eventually, they were able to dig out and refurbish the second chamber to make it work for us the way it used to, even to the extent of putting back a lot of the old metalwork like sewage pipes, which were originally glazed, and actually contributed to the chamber's acoustic qualities!"

According to Emerick, even the fact that the pipework received a gloss paint instead of an authentic glazed finish was an important audio factor, and with more recent building work affecting the size of the chamber, the decay time is minutely shorter than it was 30 years ago. "But it still colours the vocals in the same pleasant way," confirms Emerick. "It's not an obvious echo. It's odd, because you can put a bit of it around vocals and you get used to it, thinking that there isn't any echo on there at all. But when you remove the effect, you can really hear the difference".

The Abbey Road acronym for its own echo technique invention was STEED (Send Tape Echo Echo Delay) which, Emerick explains, has been adopted once more for the Anthology sessions. "The process involved us delaying the signal into the chamber via a tape machine; it was effectively delayed as a send. The signal which was to be echoed was sent to the quarter‑inch machine, and we would take the signal from the replay head, send it to one speaker in the chamber, with two condenser mics picking up the sound, and then return it to the console. We've gone about it in the same way this time, with a JBL speaker in the chamber".

One would imagine that by effectively returning to the '60s for this project, Emerick would have needed to 'unlearn' the more modern techniques he has acquired over the past 25 years. But he insists that the basic techniques he developed during the Beatles era have remained the backbone of his considerable skills. "I have fought very shy of being pushed into using a lot of modern devices. Many of today's machines and processors are based on the sounds we used to achieve mechanically, but they don't sound the same. We can do things the old way quite easily. We haven't really progressed that far; if anything it's the opposite. The original four‑track masters are one‑inch tape, so every track is a quarter‑inch wide and there is no noise. The quality of the bass is outstanding; you can't create that now. It's the same with the snare and bass drum sounds, which are so natural it's uncanny."

After George Martin's early autumn break for concert tours of Sweden and Portugal, and Emerick's two‑month stay at Dublin's Windmill Lane Studios, where he engineered Elvis Costello's forthcoming album, mixing work on The Beatles' later material resumed at Abbey Road in mid‑October. During the pair's absence, second engineer Paul Hicks (son of The Hollies' Tony Hicks) assembled rough mix templates for the remaining CDs. "Paul is a very capable engineer," comments Emerick. "It's quite ironic that I am working with him, because I was the second engineer on The Hollies' EMI audition session! If there is anything that Paul has done which sounds wrong to me, I have the opportunity to remix it, but I have a deadline to complete it before the end of November."

Come Together: The New Beatles Songs

For many, one of the most interesting parts of the Anthology story is the way the first all‑new Beatles tracks since 1970 have been put together for the project. The idea developed from an earlier suggestion that the surviving Beatles should record some incidental music to accompany the Anthology television documentary. Ringo Starr continues the tale: "Eventually, Yoko came up with a handful of tapes that John had made just before he died, and the suggestion was made that the three of us add our own bits to them and finish them off."

Suddenly, in early 1994, rumours of a bona‑fide Beatles reunion were fast becoming reality with Paul McCartney's private studio reserved as the venue (see separate box on the McCartney studio) and Geoff Emerick booked for the engineering duties. But one major piece of the jigsaw was missing: George Martin. In a recent magazine interview with McCartney, it was inferred that Martin declined the invitation to produce the recordings on the grounds of his diminished hearing. While he may agree that his hearing is not was it once was, Martin insisted that he was never asked to be involved.

"But," he says, "I'm not at all unhappy about it. I mean, The Beatles are very good record producers, and they don't need me anymore. They wanted to keep this project down to themselves as much as possible. I knew about it, I knew it was happening and there was no rancour about it. In any case, I'm now quite old [Martin is 69], and I don't want to spend the rest of my life in the recording studio. It takes too long to do things now, and there are so many other things I'd rather be doing."

The two Lennon songs to which fresh material has been added are 'Free As A Bird' (written by Lennon in 1976 after being awarded his much battled‑for US Green Card), completed by McCartney, Harrison and Starr in February 1994, and 'Real Love', which was conceived during Lennon's 'househusband' years of the late 1970s. The latter was completed by the three Beatles in February 1995. Starr says: "The only trouble was that it was John singing along to a piano, and recorded in mono on a cassette. Firstly, the recording wasn't that wonderful, and it wasn't like you could pull a fader and change each of the voice and piano levels. All we had to work with was what we heard — and it wasn't in time either."

Just Like Starting Over

Stepping into George Martin's shoes, and fulfilling a lifetime's ambition, was ex‑ELO leader‑turned‑successful producer Jeff Lynne — a natural choice in many minds. He was invited to produce the new material, having already gained several brownie points with his work on Harrison's 1987 hit album Cloud Nine. But surely, working with Lennon's rough demos to create a high‑quality result must have been extraordinarily difficult.

Lynne says: "It was very difficult, and one of the hardest jobs I've ever had to do, because of the nature of the source material; it was very primitive‑sounding, to say the least. I spent about a week at my own studio cleaning up both tracks on my computer, with a friend of mine, Marc Mann, who is a great engineer, musician and computer expert.

Jeff Lynne on the new Beatles tracks: "What we were trying to do was create a record that was timeless, so we steered away from using state‑of‑the‑art gear...while it sounds fresh and new, it wouldn't have been out of place on The White Album."

"We tried out a new noise reduction system, and it really worked. The problem I had with 'Real Love' was that not only was there a 60 cycles mains hum going on, there was also a terrible amount of hiss, because it had been recorded at a low level. I don't know how many generations down this copy was, but it sounded like at least a couple. So I had to get rid of the hiss and the mains hum, and then there were clicks all the way through it. When we saw the graph of it on the computer, there were all these spikes happening at random intervals throughout the whole song. There must have been about 100 of them. We'd spend a day on it, then listen back and still find loads more things wrong. But we would magnify them, grab them and wipe them out. It didn't have any effect on John's voice, because we were just dealing with the air surrounding him, in between phrases. That took about a week to clean up before it was even usable and transferable to a DAT master. Putting fresh music to it was the easy part! 'Free As A Bird', however, wasn't a quarter as noisy as 'Real Love' and only a bit of EQ was needed to cure most problems."

Timing must have been a problem, because Lennon was never one for keeping in time with himself. "Well, nobody is when they're just writing a song. You don't think, 'I'd better use a click while I'm putting down this idea.' You just play and enjoy yourself. So it took a lot of work to get it all in time so that the others could play to it. It's quite a complex process, but for some reason, I kind of know how to do it, through messing around on other stuff for years."

We Can Work It Out

When Lynne brought the 'treated' Lennon DATs to McCartney's studio for the overdub sessions, all concerned were adamant that analogue equipment and die‑hard techniques should be used wherever possible. With McCartney's studio unsurprisingly well‑stocked with a Neve console, generous vintage outboard and Neumann U47s for vocals, the only specialised item of equipment required from the outside world was an Oberheim OBX8 analogue synth for what Lynne describes as "a soft, synthesized pad sound, played by Paul." He adds: "What we were trying to do was create a record that was timeless, so we steered away from using state‑of‑the‑art gear. We didn't want to make it fashionable. It's just making the statement that they are all here playing together after all these years. So while it sounds fresh and new, it wouldn't have been out of place on The White Album."

What was a surprise, however, was the absence of McCartney's trademark Hofner violin bass. Lynne says: "Paul played his Wal five‑string on 'Free As A Bird' and on 'Real Love' he used his double bass (originally owned by Elvis Presley's bassist, Bill Black) — and we tracked it with a Fender Jazz. Paul went DI to the desk, but also used his Mesa Boogie amp and we took a mixture of the two signals. George used a couple of Strats — a modern, Clapton‑style one (Lace Sensors) and his psychedelic Strat that's jacked up for the bottleneck stuff on 'Free As A Bird'. They also played six‑string acoustics — Paul chose his Gibson jumbo while George used a smaller Martin, and Ringo played his Ludwig kit, so there are genuine Beatles drums on there."

A celebrated motor racing enthusiast, Harrison chose to use his unusual McLaren guitar amp for the sessions. Geoff Emerick: "It's true! When George took delivery of his McLaren car, the company made him an amplifier that fitted into the luggage compartment. It actually comes out of the car, and it's a great little amp. He used that a lot on the sessions. I think it's a Fender inside, but it's covered in all the McLaren fabric and colours."

The three Beatles began work in February on a third unfinished Lennon demo. Contrary to press speculation, this song was not 'Grow Old With Me' but one which Lynne and Emerick recall being titled either 'Now And Then' or 'Miss You' — a track which Emerick expects the remaining Beatles to complete in the not too distant future. He says: "We did start work on it, but it was obviously unfinished from a writing point of view, so we thought we'd work on 'Real Love' which had a complete set of words. It'll need to be completed as a song before everybody decides what to do with it, and," he adds with a grin, "it's not hard to imagine who would finish writing it."

From Them To You

Of his time spent with The Beatles, Lynne says: "Being right there in the inner sanctum and hanging out with them for a few weeks was fantastic. Although a long time has passed since they last recorded as one unit, they worked terribly well together, and being in the control room watching and listening to them interact with each other was fascinating. I'd often have cause to think, 'Christ, no wonder they were the best.' But I always thought they were the greatest anyway.

"They're still great musicians and great singers. Paul and George would strike up the backing vocals — and all of a sudden it's The Beatles again! To be there in the middle of all this and have a degree of responsibility over the result was astonishing. It wasn't some kind of fake version, it really was the real thing. They were having fun with each other and reminding each other of the old times. I'd be waiting to record and normally I'd say, 'OK, let's do a take', but I was too busy laughing and smiling at everything they were talking about."

As well as directing from the control room, Lynne also contributed a vocal harmony and a guitar overdub on 'Free As A Bird'. "But," he says, "I wanted to keep my hands off as much as possible. The only things I really did were the funny little bits at the end of the track. I made sure that whatever was done as a big part of the record was them."

For Beatle fan Lynne, it must have felt like everything he had achieved in his entire career had led to this ultimate experience. Was it like The Twilight Zone? "Sometimes! I'd get up in the morning and think, 'God, I'm working with The Beatles today, I can't believe it!'. It was a lovely, magical time. But as well as being the ultimate musical pleasure and thrill, the thought of it was very scary, because it had never been done before, and there were no points of reference. You know, what do you do on a Beatles record when the singer's not there?"

Paul McCartney agrees: "It was quite spooky and emotional at first, listening to John's voice and seeing each other working again in the same room after so long, but it turned out to be wonderful. We decided the best way to handle it was to imagine that John had gone on holiday and asked us to finish off his tracks. For me, even though we worried a little about what it would be like, and it took a lot of organising, the greatest thing was that we worked so well and it was so cool."

Despite previous reservations, George Martin, too, is pleased with the outcome. "What they did with John's tapes is exceptionally clever and very good. It will be well received, because it's a very good song, and well‑produced. If The Beatles had been alive as a group today, it's exactly the kind of thing they'd have done. It's not retro, it's not something they would have done in the 1960s. I think it's awfully good, but although they had great fun doing it, it's not the beginning of a new career for them. I think we've all looked upon it as a good addendum to what we've done with the Anthology."

The Long And Winding Road

The next two Anthology double CD sets will become available during the first half of 1996. These releases are likely to include priceless rarities such as the first take of 'Strawberry Fields Forever' (see the 'Strawberry Fields Revisited' box elsewhere in this article), a composite orchestra‑less version of 'A Day In The Life', spliced together from two early takes, experimental Revolver outtakes, alternate versions of songs from the so‑called White Album (see the box on Chris Thomas), including a beautiful acoustic performance of George Harrison's 'While My Guitar Gently Weeps', and grass roots jamming from the Let It Be movie sessions.

The Anthology project may not provide the world with everything The Beatles recorded but, as Martin says, "It will be a good, solid chunk of stuff they haven't heard before." I ask him if this project will signify the end of his professional career as The Beatles' producer, and with a wry smile on his face he replies, "Probably. It's amazing that it's lasted this long. I'm very proud of what we've done, and it has stood the test of time incredibly well."

Martin & Emerick — An Awesome Partnership

16‑year‑old Geoff Emerick first made himself known to George Martin as his second engineer on Rolf Harris's 'Sun Arise' in 1962. He made his debut in The Beatles' camp as the tape operator‑cum‑assistant engineer on an Abbey Road Studio One session on 20 February 1963, when George Martin overdubbed various keyboard parts on tracks for the group's debut album, Please Please Me. Emerick went on to assist on a number of Beatles sessions over the following 18 months, but his big break came in the spring of 1966, when he was promoted to the role of George Martin's right‑hand man at the start of the Revolver sessions. Little more than a year later, he was awarded a Grammy for his sterling work on Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Martin says: "Geoff and I have known each other for more years than we care to remember. My previous engineer, Norman Smith, wanted to become a producer and work with another group, but he also wanted to continue working with me and The Beatles. I thought he was right to look towards a career as a producer and I would help him out in any way I could, but I told him it wouldn't work out to also carry on as my engineer. The person who works as my engineer has to give me absolute priority over everything, and I won't accept anything less than 100%. Norman understood and he left the team.

"So I had to look around for his replacement, and I remembered Geoff being very bright, with a good ear for sound, so I chucked him in the deep end. In fact 'Tomorrow Never Knows' was the first Beatles session he worked on as my engineer [on 6 April 1966 — Ed]."

Emerick says: "I was far from being a total novice, because I had already engineered the 'Pretty Flamingo' hit for Manfred Mann, with John Burgess producing. I got called into the office one day and was asked if I wanted the job with George. I was playing mind games with it for a while but eventually went for it. When I joined EMI at 16, there was no way that you would become a recording engineer until you were 40. So the changes that were happening at Abbey Road were quite drastic."

Midge Ure once described working with Martin and Emerick as being in the company of two wise professors. Emerick appreciates the comment. "Yes, I suppose we can come across like that. Having worked with George for so long, I can normally read his mind. So we tend not to talk to each other much at sessions. To me, George's forte has always been working out vocal harmonies. Many of The Beatles' arrangements were their ideas which he then transferred to paper and helped to modify, but he is a great arranger in his own right and I would have liked to see him do more."

"We've obviously got to know each other pretty much inside out," says Martin. "We have always been a very good team."

Audio Alchemy: The Beatles And Studio Techniques

While The Beatles' approach to songwriting alone redefined pop music several times over in their relatively short career, it was their steadfast unwillingness to accept the words 'it can't be done' that magically transformed the recording studio from a simple vehicle for capturing performances on tape into a playhouse for boundless creativity. In effecting this transformation, they shaped the future of record production, and their influence and techniques continue to be as relevant in today's rock and pop world as they were 30 years ago. "A series of massive quantum leaps" is how George Martin describes the progress of The Beatles as studio artists, and one should remember that less than three years separated the group's 'Yeah, yeah, yeah' beat pop of 1963 and work like the mind‑blowing, extra‑terrestrial‑sounding 'Tomorrow Never Knows'.

As Head of A&R at Parlophone, then EMI's light entertainment and jazz label, Martin was already experienced in the world of sound effects, and had used them on a number of records before The Beatles' arrival at his door in 1962. He says: "I introduced The Beatles to different tape speeds and reversing tapes, all that kind of thing. They didn't know anything about that, and as soon as I showed them something new and weird, they would get enormously enthusiastic about it. I remember explaining to them how you could make a piano sound different, and that got them very excited. You could almost see their minds working overtime and thinking, 'How can we apply this to our recordings?' But it was Paul's idea to use tape loops on 'Tomorrow Never Knows' — and it was a very good idea too. They loved doing anything that was different, and from quite early on it was a constant search for new sounds and new instruments."

Nothing could have prepared Geoff Emerick for the swift change of gear in The Beatles' recording habits that was to accompany his debut as their engineer, as they began work on the Revolver album. "But I did have some ideas that appealed to them," he says. "I was listening to some American records that impressed me, and I didn't really know how they got those sounds. But I tried to change the miking technique that I was taught here, thinking that was what it took to achieve a certain sound. I began moving a lot closer with the mics, and we started taking the front skin off the bass drum. There was a rule here then that you couldn't place the mic closer than 18 inches from the bass drum, because the air pressure would damage the diaphragm. I had to get a letter from the management which gave me permission to do go in closer with the mic on Beatles sessions. I then went about completely changing the miking techniques, and began to over‑compress and limit things heavily.

"Revolver was the first time we put the drums through Fairchild limiters, and that was just one example of the things that the other Abbey Road engineers used to hate, because they had done it a certain way for so many years — so why change it? But The Beatles were screaming out for change. They didn't want the piano to sound like a piano anymore, or a guitar to sound like a guitar. I just had to screw around with what we had."

New‑fangled Abbey Road inventions which were to emerge during the Revolver sessions included ADT (Artificial Double Tracking), and its sister, flanging — both then manual techniques brought back to life once more for the Anthology by Emerick. "ADT happened as a result of John asking why he had to sing a part twice to double‑track it. We realised that if we took the information off the sync head of the multitrack machine as we were mixing, we could advance it before the replay head on to a quarter‑inch machine and use varispeed to create a ghost image on top of the original sound. We would often move the distance between the two signals by altering the oscillators, and that was what we called flanging. The name seems to have stuck!"

McCartney's bass sound also took on a new life during 1966 and '67. Emerick says: "We never really got anywhere with DI‑ing the bass. On Sgt. Pepper, particularly, we would always reserve one track of the four‑track tape for Paul's bass overdubs. He used to stay behind some nights with me just for that purpose. We would put his bass amp in the middle of Studio Two, and mike it from about eight feet away with an old valve C12, and sometimes use a second mic even further away and mix the two signals together. You can hear that on some of the Pepper tracks, where there is a slightly different quality about the bass."

Strawberry Fields Revisited

One of the gems awaiting fans in the later volumes of the Anthology project will be the first take of 'Strawberry Fields Forever'. Quite unlike the released single, this gorgeous version was first heard publicly as part of London Weekend Television's 1992 documentary, The Making Of Sgt. Pepper. George Martin recalls the session: "The whole format is different to the finished version, in that it has no introduction, and starts with the verse instead of the chorus hook. But even that wasn't the way I heard it originally. The first time I heard the song was when I listened to John singing and playing it on an acoustic guitar. John was very Dylanish in many ways, but he had that lovely voice, which I think was much better than Dylan's. Just to hear his voice with a simple guitar backing was absolutely delightful, and I wish we had been able to record a version like that — the way I first heard it."

'Strawberry Fields Forever' was notable for one of the earliest, most imaginative uses of the fabled Mellotron — an instrument which Martin appears to love to hate. "It was a bastard of an instrument really, an early attempt at a synthesizer, although it had more in common with today's sampling devices. The sound we used on 'Strawberry Fields' was supposed to be a real flute, but no flautist would ever play like that! But it was a great sound, and it's impossible to hear it any other way now. Instead of using the Mellotron to reproduce authentic instruments, we took it for what it was, and used it more interestingly."

I asked Geoff Emerick whether, as with 'Strawberry Fields' there are different versions of other tracks from the period, and whether these might be sufficient to form, say, an alternative Sgt. Pepper album. He replied: "Unfortunately not. We were overdubbing four‑track to four‑track, and the only things that would have existed were other takes of the rhythm tracks. We only overdubbed on to the best rhythm track of each song, so there wouldn't be complete alternate versions".

Paul McCARTNEY'S Studio

Built to his discerning specifications in the mid‑1980s, Paul McCartney's private studio includes a battery of equipment that reflects the best he has worked with in the UK and America. The slope‑sided, triangular‑shaped control room (approximately 30 feet at its widest point and 25 feet deep) houses a Neve V‑Series console fitted with favoured EQ modules from an older Neve desk, as well as Focusrite EQ and mic amp modules. Outboard equipment includes regular items, such as a Lexicon 224X reverb, but among the more vintage units is a Fairchild valve compressor. Microphones include classic Neumann U47s, which proved invaluable during the 'new' Beatles vocal sessions. At the end of the signal path are two Studer A800 24‑track machines and a Mitsubishi 32‑track digital recorder. Tracks recorded there are normally mixed down to DAT and half‑inch tape.

Apart from being the recording venue for his albums Flowers In The Dirt (1989), Off The Ground (1993) and the new Beatles tracks, the studio also recently played host to another amazing Beatle‑orientated session. Paul and Linda McCartney, together with their children, Heather, Mary, Stella and James (on guitar), contributed to Yoko Ono's emotional song, 'Hiroshima Sky Is Always Blue', which also featured a performance by John Lennon's 20‑year‑old son, Sean.

Sonic Therapy: Jeff Lynne On Recording Techniques

A master of vocal recording techniques, Jeff Lynne is celebrated for his unique treatment of acoustic guitars. "I have a certain technique for recording acoustics which is slightly unusual. When you've got a bunch of acoustics jangling away together, there might be a tiny difference in tuning and you get a really nice, big, warm sound. Sometimes, I'll double that straight away, and maybe do both takes in mono, so that there's one set of guitars on the left and another set on the right. It sounds stereo, because it's two separate performances.

"I don't use much compression on acoustics, because when you record a bunch of guitars like that, it results in a lot of harmonic distortion. I keep them as clean as I can until the last minute when I'm mixing — then anything can happen! I tend to use compression on other things, like pianos. I compress the hell out of them, because that's the sound I like. I get a really big sound when I mic a piano from about 15 feet away, then really compress it hard. I mic the acoustics fairly normally — about a foot away."

"I like to use real drums as much as possible, especially when everyone knows the songs well. In the worst possible situation, where there is just a click and nothing else to work from, I have occasionally used samples from my own collection of bass drum and snare sounds — but on nearly everything I've done there is a real, human drummer."

These days, Lynne favours a minimalistic approach to recording vocals, and is often satisfied with just one double‑tracked voice. This, however, was not always the case. "I went through a long phase where I had to have everything sounding like a choir and double‑tracked everything at least four times so it became nice and thick. I very rarely used echo although I often used slapback, but not reverb. If I'm known for anything, I suppose it's for making dry records. I just prefer to have a close‑up vocal with no echo. I have made some wettish‑sounding tracks in the past, but certainly over the last six to eight years, the records I have made have sounded pretty natural."

Chris Thomas & The White Album

The later installments of the Anthology CD series, due in early 1996, are set to include several alternative takes of songs from the celebrated double album The Beatles — otherwise known as The White Album. At the time of its November 1968 release, a new name was seen on the credits: Chris Thomas. A graduate of George Martin's AIR production company stable and now one of Britain's most respected rock producers, Thomas was a mere 21 when he 'produced' a handful of sessions for the album while Martin went on holiday.

Thomas recalls: "In March 1968, George gave me a job with AIR on six months' trial, which I got through. I was put on a three‑year contract. The first time I was ever allowed in the studio control room on my own was the time I came back from holiday and George had just gone away on his, leaving a note saying, 'Go down to The Beatles' sessions.' This was in September 1968 — they had already been recording The White Album for about three months.

"I automatically assumed that I'd go down there as normal, sit in the corner and not really do anything. But no! Paul walked in and asked me what I was doing there. I thought that there was no way George would have landed me in it, and would have warned them of what was happening. So I said, 'George told me to come down, didn't you know?' Paul just looked me in the eye and said, 'Oh well, if you want to produce us, fine, and if you don't, we'll just tell you to fuck off.' And he walked out! I don't think I said a word for ages after that. I just froze because they all sort of rolled up. Ken Scott had taken over from Geoff Emerick because he couldn't stand the strained atmosphere and didn't want to continue with it. I sat down next to Ken and they started doing a take of 'Helter Skelter'. I was getting completely blanked by them. I thought, 'Christ, not only am I going to get elbowed and told not to come back after tonight, but that's also going to reflect on my job with George.'

"So I just jumped in at the deep end. They were doing a take, and somebody made a little cock‑up. I said, 'Something went wrong there.' They said, 'No it didn't!' But they all came up the stairs to listen and agreed. I just took the bull by the horns and cracked the whip. It sounds extraordinary, but it was only out of total fear that I did it, not anything else. We had started at about 2.30 in the afternoon and finished at 2.30 in the morning, and by the end of the evening, I said to Paul, 'What happens about tomorrow?' He said, 'If you want to come down it's alright.' I thought, 'He didn't say piss off. Wow!' So I came back the next day, and they did a wind‑up. They were doing the backing vocals on 'Helter Skelter', those 'aaaahs' that you hear — four tracks of backing vocals. It was John, George and Paul doing a three‑part harmony, and then they double‑tracked it twice to get twelve voices. On the last time, they flicked one of the mics around, so it only picked up two on one side and one on the other. I said, 'That sounds great, come up and have a listen.' Paul said, 'Hang on a minute, the mic sounds like it's switched off on this side.' I said, 'Well, it sounds alright, because you can't tell the difference between 11 and 12 voices.' It was little things like that that were designed to test me. I was definitely being severely wound up! It was like, 'are we going to let this imposter in?'

"It was great how it ended up, because they were sticking me on everything. They were saying, 'Oh, he's here, he can play that'. I played harpsichord on 'Piggies'. Piano on 'Long Long Long'. Organ on 'Savoy Truffle'. Mellotron on 'Bungalow Bill': the mandolin sounds for the verses and the trombone sound for the choruses. That was something else; I was in Number Two at Abbey Road, playing live with The Beatles. Crazy! And there were other things; while Paul was working on an overdub in Studio Two, John and I would go to another part of Abbey Road to track down some sound effects, which we did for 'Blackbird'.

"It was my idea to use the harpsichord on 'Piggies'. The harpsichord was set up in Number One studio for a classical session. I went in there and I was playing away, thinking how good it sounded. I knew we were going to do 'Piggies', so I went in to see George Harrison and said, 'There's a harpsichord in there, do you fancy using it on your song?' He sat down with me and he started playing me this song called 'Something'. I said, 'That's fantastic — why don't you do that instead?' He just said, 'Do you really like it? I'll give it to Jackie Lomax as a single then!' [George, fortunately, changed his mind later, and 'Something' became a hit for the Beatles. When Frank Sinatra heard it, he described it as the greatest love song of the previous 50 years — Ed.]

"Anyway, we started to push the harpsichord out of Number One and into Number Two, and Ken Scott looked horrified. He said, 'What the hell are you doing?!' I hadn't realised what they did in Number One with recordings of classical sonatas. They'd have a session one day, then leave the harpsichord in exactly the same place, tune it up perfectly the next morning, and then continue the recording. So you weren't allowed to move this thing at all. In the end, we moved it back into Number One, as close to where I'd found it as possible, and everyone went in there to record it.

"I had the wonderful job of wobbling the oscillator for Eric Clapton's guitar on 'While My Guitar Gently Weeps' while it was being mixed. Apparently Eric had insisted that his guitar should sound a bit different to the normal Clapton. That keyboard sound was a flanged organ — very whiny and slightly out of tune. There were loads of things like that. Consequently, I learned such a lot from those sessions in terms of adding detail and also how you could just play with stuff without taking the tracking side too seriously. You'd take it more seriously later and pay attention on the mix.

"It was almost like being a child with The Beatles. That innocent feeling of trying out loads of different things to see what worked — throwing ideas in the air and seeing what happened without sticking to a rigid plan. I certainly learned that you had to abuse your equipment to achieve a certain sound. There were no boxes around then to do it for you."

The End: George Martin On The Making Of Abbey Road

George Martin's television programme, The Making Of Sgt Pepper, and its spin‑off book, Summer Of Love, are evidence that the world's most famous album remains his proudest moment as a producer. But it is the final album the Beatles made, Abbey Road, recorded during the summer of 1969, which he feels is the group's greatest musical achievement. "It's very dear to my heart, because after all the trauma of Let It Be, we really got it together," says Martin.

"When we did Let It Be I just thought it was the end; and what a sad way it would have been to have gone like that, because from Sgt Pepper I thought we were pointing the way to a new style of recording. We were establishing a trend and I wanted to follow it up, but Let It Be was recorded in a quite different way. When I was asked to come back and produce another album, I didn't believe that it would work out. I told Paul that I wasn't sure that I wanted to do it. I said, 'I'll only do it if I'm really allowed to do it the way we used to.' He assured me that everybody was very keen, and I went along with it.

"Abbey Road was the development of my own idea to establish something of a classical form in rock 'n' roll music, and I urged John and Paul to think of their songs as subjects in a symphony, using them more than once in different keys, have them in counterpart with each other, and make up a longer work. One side of Abbey Road does reflect that. The other side doesn't — but it was a good compromise, I thought."

The great irony of Abbey Road is that although it sounds like four great friends making joyous music, they were very close to breaking up. Martin says: "They really did work well together, and the disharmony of their private and business lives was put aside. I think they all knew that it was to be their last album, so, maybe subconsciously, there was a drive to make it a really good one. My memories of the sessions are all happy ones".

What Goes On: Anthology Volume I

As this article was being prepared for publication, EMI and Apple Records announced the final track listing for Volume 1 of the Anthology project. Some of the tracks (marked <S>) are actually sections of speech cut from old interviews. The album will contain over 60 tracks, including the spoken word items.

COMPACT DISC 1

Free As A Bird

"We Were Four Guys..." <S>

That'll Be The Day

In Spite Of All The Danger

"Sometimes I'd Borrow..." <S>

Hallelujah, I Love Her So

You'll Be Mine

Cayenne

"First Of All..." <S>

My Bonnie

Ain't She Sweet

Cry For A Shadow

"Brian Was A Beautiful Guy..." <S>

"I Secured Them..." <S>

Searchin'

Three Cool Cats

The Sheik Of Araby

Like Dreamers Do

Hello Little Girl

"Well, The Recording Test..." <S>

Besame Mucho

Love Me Do

How Do You Do It

Please Please Me

One After 909 (Sequence)

One After 909 (Complete)

Lend Me Your Comb

I'll Get You

"We Were Performers..." <S>

I Saw Her Standing There

From Me To You

Money (That's What I Want)

You Really Got A Hold On Me

Roll Over Beethoven

COMPACT DISC 2

She Loves You

Till There Was You

Twist And Shout

This Boy

| Want To Hold Your Hand

"Boys, What I was Thinking..." <S>

Moonlight Bay

Can't Buy Me Love

All My Loving

You Can't Do That

And I Love Her

A Hard Day's Night

I Wanna Be Your Man

Long Tall Sally

Boys

Shout

I'll Be Back (Take 2)

I'll Be Back (Take 3)

You Know What To Do

No Reply (Demo)

Mr Moonlight

Leave My Kitten Alone

No Reply

Eight Days A Week (Sequence)

Eight Days A Week (Complete)

Kansas City/Hey Hey Hey

The album will be released on November 21st, 1995, and will be followed, on November 26th, by the first 60‑minute part of the 6‑hour Anthology TV documentary, to be screened on ITV.

Source: https://www.soundonsound.com/people/story-beatles-anthology-project