7th April 2009

THE BEATLES' ENTIRE ORIGINAL RECORDED CATALOGUE REMASTERED FOR RELEASE 09-09-09

Apple Corps Ltd. and EMI Music are delighted to announce the release of the original Beatles catalogue, which has been digitally re-mastered for the first time, for worldwide CD release on Wednesday, September 9, 2009 (9-9-09), the same date as the release of the widely anticipated "The Beatles: Rock Band" video game. Each of the CDs is packaged with replicated original UK album art, including expanded booklets containing original and newly written liner notes and rare photos. For a limited period, each CD will also be embedded with a brief documentary film about the album. On the same date, two new Beatles boxed CD collections will also be released.

The albums have been re-mastered by a dedicated team of engineers at EMI's Abbey Road Studios in London over a four year period utilising state of the art recording technology alongside vintage studio equipment, carefully maintaining the authenticity and integrity of the original analogue recordings. The result of this painstaking process is the highest fidelity the catalogue has seen since its original release.

The collection comprises all 12 Beatles albums in stereo, with track listings and artwork as originally released in the UK, and 'Magical Mystery Tour,' which became part of The Beatles' core catalogue when the CDs were first released in 1987. In addition, the collections 'Past Masters Vol. I and II' are now combined as one title, for a total of 14 titles over 16 discs. This will mark the first time that the first four Beatles albums will be available in stereo in their entirety on compact disc. These 14 albums, along with a DVD collection of the documentaries, will also be available for purchase together in a stereo boxed set.

Within each CD's new packaging, booklets include detailed historical notes along with informative recording notes. With the exception of the 'Past Masters' set, newly produced mini-documentaries on the making of each album, directed by Bob Smeaton, are included as QuickTime files on each album. The documentaries contain archival footage, rare photographs and never-before-heard studio chat from The Beatles, offering a unique and very personal insight into the studio atmosphere.

A second boxed set has been created with the collector in mind. 'The Beatles in Mono' gathers together, in one place, all of the Beatles recordings that were mixed for a mono release. It will contain 10 of the albums with their original mono mixes, plus two further discs of mono masters (covering similar ground to the stereo tracks on 'Past Masters'). As an added bonus, the mono "Help!" and "Rubber Soul" discs also include the original 1965 stereo mixes, which have not been previously released on CD. These albums will be packaged in mini-vinyl CD replicas of the original sleeves with all original inserts and label designs retained.

Discussions regarding the digital distribution of the catalogue will continue. There is no further information available at this time. Source: thebeatles.com

Additional mastering information:

The Stereo Albums (available individually and collected in a stereo boxed set)

The stereo albums have been remastered by Guy Massey, Steve Rooke, Sam Okell with Paul Hicks and Sean Magee

All CD packages contain original vinyl artwork and liner notes

Extensive archival photos

Additional historical notes by Kevin Howlett and Mike Heatley

Additional recording notes by Allan Rouse and Kevin Howlett

* = CD includes QuickTime mini-doc about the album

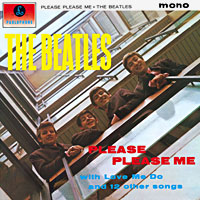

Please Please Me* (CD debut in stereo)

With The Beatles* (CD debut in stereo)

A Hard Day's Night* (CD debut in stereo)

Beatles For Sale* (CD debut in stereo)

Help!*

Rubber Soul*

Revolver*

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band* (also includes 1987 notes, updated, and new intro by Paul McCartney)

Magical Mystery Tour*

The Beatles*

Yellow Submarine* (also includes original US liner notes)

Abbey Road*

Let It Be*

Past Masters (contains new liner notes written by Kevin Howlett)

'The Beatles in Mono' (boxed set only)

The mono albums have been remastered by Paul Hicks, Sean Magee with Guy Massey and Steve Rooke

Presented together in box with an essay written by Kevin Howlett

+ = mono mix CD debut

Please Please Me

With The Beatles

A Hard Day's Night

Beatles For Sale

Help! (CD also includes original 1965 stereo mix)+

Rubber Soul (CD also include original 1965 stereo mix)+

Revolver+

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band+

Magical Mystery Tour+

The Beatles+

Mono Masters

Re-mastering the Beatles catalogue

The re-mastering process commenced with an extensive period conducting tests before finally copying the analogue master tapes into the digital medium. When this was completed, the transfer was achieved using a Pro Tools workstation operating at 24 bit 192 kHz resolution via a Prism A-D converter. Transferring was a lengthy procedure done a track at a time. Although EMI tape does not suffer the oxide loss associated with some later analogue tapes, there was nevertheless a slight build up of dust, which was removed from the tape machine heads between each title.

From the onset, considerable thought was given to what audio restorative processes were going to be allowed. It was agreed that electrical clicks, microphone vocal pops, excessive sibilance and bad edits should be improved where possible, so long as it didn't impact on the original integrity of the songs.

In addition, de-noising technology, which is often associated with re-mastering, was to be used, but subtly and sparingly. Eventually, less than five of the 525 minutes of Beatles music was subjected to this process. Finally, as is common with today's music, overall limiting - to increase the volume level of the CD - has been used, but on the stereo versions only. However, it was unanimously agreed that because of the importance of The Beatles' music, limiting would be used moderately, so as to retain the original dynamics of the recordings.

When all of the albums had been transferred, each song was then listened to several times to locate any of the agreed imperfections. These were then addressed by Guy Massey, working with Audio Restoration engineer Simon Gibson.

Mastering could now take place, once the earliest vinyl pressings, along with the existing CDs, were loaded into Pro Tools, thus allowing comparisons to be made with the original master tapes during the equalization process. When an album had been completed, it was auditioned the next day in studio three - a room familiar to the engineers, as all of the recent Beatles mixing projects had taken place in there - and any further alteration of EQ could be addressed back in the mastering room. Following the initial satisfaction of Guy and Steve, Allan Rouse and Mike Heatley then checked each new re-master in yet another location and offered any further suggestions. This continued until all 13 albums were completed to the team's satisfaction.

New Notes/Documentaries Team

Kevin Howlett (Historical and Recording Notes)

Kevin Howlett's career as an award-winning radio producer spans three decades. His music programmes for the BBC have included many documentaries about The Beatles, including 'The Beeb's Lost Beatles Tapes.' He received a Grammy nomination for his involvement with The Beatles' album 'Live At The BBC' and, in 2003, produced the 'Fly On The Wall' bonus disc for 'Let It Be... Naked.'

Mike Heatley (Historical Notes)

Mike entered the music business via HMV Record Stores in 1970, transferring to EMI Records' International Division three years later. He eventually headed up that division in the early Eighties before joining the company's newly created Strategic Marketing Division in 1984. In 1988, he returned to International, where he undertook a number of catalogue marketing roles until he retired in December 2008.

During his career he worked with many of EMI's major artists, including Pink Floyd, Queen, Kate Bush and Iron Maiden. However, during the last 30 years he has formed a particularly strong relationship with Apple, and has been closely involved in the origination and promotion of the Beatles catalogue, besides solo releases from John, Paul, George and Ringo.

Bob Smeaton (Director, Mini-Documentaries)

Bob Smeaton was series director and writer on the Grammy award winning 'Beatles Anthology' TV series which aired in the UK and the USA in 1995. In 1998 he received his second Grammy for his 'Jimi Hendrix: Band of Gypsys' documentary. In 2004 he gained his first feature film credit, as director on the feature documentary 'Festival Express.' He subsequently went on to direct documentaries on many of the world's biggest music acts including The Who, Pink Floyd, The Doors, Elton John, Nirvana and the Spice Girls.

Julian Caiden (Editor, Mini-Documentaries)

Julian has worked with Bob Smeaton on numerous music documentaries including 'Jimi Hendrix: Band of Gypsys' and the 'Classic Albums' series, featuring The Who, Pink Floyd, The Doors, Elton John and Nirvana among others. He has worked on documentary profiles from Richard Pryor to Dr. John to Sir Ian McKellen, Herbie Hancock and Damien Hirst and on live music shows including the New York Dolls and Club Tropicana.

The Abbey Road Team

Allan Rouse (Project Coordinator)

Allan joined EMI straight from school in 1971 at their Manchester Square head office, working as an assistant engineer in the demo studio. During this time he frequently worked with Norman (Hurricane) Smith, The Beatles' first recording engineer.

In 1991, he had his first involvement with The Beatles, copy¬ing all of their master tapes (mono, stereo, 4-track and 8-track) to digital tape as a safety backup. This was followed by four years working with Sir George Martin as assistant and project coordinator on the TV documentary 'The Making of Sgt. Pepper's' and the CDs 'Live at the BBC' and 'The Anthol¬ogy.'

In 1997, MGM/UA were preparing to reissue the film 'Yellow Submarine' and, with the permission of Apple, asked that all of The Beatles' music be mixed for the film in 5.1 surround and stereo. Allan requested the services of Abbey Road's senior engineer Peter Cobbin and assistant Guy Massey and, along with them, produced the new mixes.

Two years later, he proposed an experimental stereo and surround mix of John Lennon's song 'Imagine' engineered by Peter Cobbin. Following lengthy consultations with Yoko Ono, the album 'Imagine' was re-mixed in stereo and the Grammy award-winning film 'Gimme Some Truth' in surround and new stereo. This led to a further five of John's albums being re-mastered with new stereo mixes and the DVD release of 'Lennon Legend' being re-mixed in 5.1 surround and new stereo.

Further projects followed, including The Beatles 'Anthol¬ogy', 'The First US Visit' and 'Help' DVD and the albums 'Let It Be...Naked' and 'Love' along with George Harrison's 'Concert for Bangladesh' DVD and album.

For a number of years now, Allan has worked exclusively on Beatles and related projects.

Guy Massey (Recording Engineer)

Guy joined Abbey Road in 1994, and five years later assisted on the surround remix for The Beatles film 'Yellow Submarine.' This led to The Beatles' 'Anthology' DVD and later, along with Paul Hicks and Allan Rouse, they mixed and produced 'Let It Be... Naked.' In 2004 he left the studios to become freelance and has engineered The Divine Comedy: 'Victory for the Comic Muse,' Air Traffic: 'Fractured Life,' James Dean Bradfield: 'The Great Western' and Stephen Fretwell's 'Magpie,' co-producing the last two. Since leaving, Guy is still a vital member of the team, and has been the senior engineer for the re-mastering project and was responsible for surround and new stereo mixes for the DVD release of 'Help!'

Steve Rooke (Mastering Engineer)

Steve joined Abbey Road in 1983 and is now the studio's senior mastering engineer. He has been involved on all The Beatles' projects since 1999. He has also been responsible for mastering releases by John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr.

Paul Hicks (Recording Engineer)

Paul started at Abbey Road in 1994, and his first involvement with The Beatles was assisting engineer Geoff Emerick on the Anthology albums. This was followed by 'Yellow Submarine Songtrack,' 'Anthology' DVD and 'Let It Be... Naked.' Like Guy Massey, he has also become a freelance engineer and since leaving the studios he has been responsible for the surround mixing of Paul McCartney's DVD 'The McCartney Years' and The Beatles' 'Love.' Paul has been in charge of the mono re-masters.

Sean Magee (Mastering Engineer)

Sean began working at Abbey Road in 1995 with a diploma in sound engineering. With a wealth of knowledge in analog and digital mastering, he has worked alongside Paul Hicks on the mono re-masters.

Sam Okell (Recording Engineer)

Sam's first job as a member of the team was in 2006, assisting Paul Hicks on Paul McCartney's DVD 'The McCartney Years,' and during that same year he was responsible for the re-mastering of George Harrison's 'Living In The Material World' CD along with Steve Rooke. This led to him restoring the soundtrack to the Beatles film 'Help!' in surround and stereo, in addition to assisting Guy Massey with the song remixes.

Sam has re-mastered 'With The Beatles' and 'Let It Be.'

Simon Gibson (Audio Restoration Engineer)

Simon joined Abbey Road in 1990. He has progressed from mastering mostly classical recordings to include a much wider range of music, including pop and rock, with his specialized role as an audio restoration engineer. Apart from the re-mastering project, his other work includes George Harrison's 'Living In The Material World,' John Lennon's 'Lennon Legend,' The Beatles' 'Love' and the 'Help!' DVD soundtrack.

You can find them here to enjoy:

http://willempie46.blogspot.com/2009/09/beatles-remastered-set-2009.html

and here for the full set:

http://www.downloadingall.org/2009/09/d-download-beatles-remastered-stereo.html

or here:

http://beatoasis.blogspot.com/2009/09/beatles-stereo-box-set-remastered-flac.html

Album Summary:

Here is an overview of each remastered album:

:: Please Please Me – “ah, one, two, three, farrrr …” counts Paul McCartney as the band open their first album with I Saw Her Standing There in 1963. Much of the album was recorded in one day and it was largely the live act of the time. Twist And Shout was left to the end of the session because of the throat-shredding effect it had on Lennon’s voice. It featured the famed cover shot of the band looking down from a balcony at EMI’s Manchester Square offices in London (recreated in 1969).

:: With The Beatles – Recorded just four months after their debut and featuring George Harrison’s first composition (Don’t Bother Me), With The Beatles contained six covers and standards, like its predecessor. Included is the track I Wanna Be Your Man, which Lennon and McCartney first wrote and donated to the Rolling Stones.

:: A Hard Day’s Night – The first album written entirely by Lennon and McCartney and featuring 12-string guitars and acoustics to enrich the sound. Written as the soundtrack to a Dick Lester-directed film of the same name, with the title coming from a “Ringo-ism”.

:: Beatles For Sale – By now the band’s lives were increasingly hectic, with touring, filming, travelling and recording – and such was the pressure that work began on this album just six days after the final session for A Hard Day’s Night. As such, the band were again relying on a number of covers with Carl Perkins and Buddy Holly tracks included. They were as worn out as they look on the Hyde Park cover shot.

:: Help! – Soundtrack to the second Beatles film with seven of the tracks used in the completed caper. Among the notable tracks are Ticket To Ride and You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away, as well as Yesterday which featured only one Beatle, Paul McCartney, plus a string quartet. Although the cover concept was to spell HELP in semaphore, it was thought the arm positions did not look good enough so the album actually spells NUJV.

:: Rubber Soul – The album which many see as the beginning of the ’interesting Beatles’, as the band play with new sounds. Norwegian Wood saw George Harrison tinkering with a sitar, while If I Needed Someone features a Byrds-y jangle and was one of a number of tracks with a country-rock feel. The cover also shows how the band were embracing psychedelia with the bubble writing and stretched photo giving a mind-expanding feel.

:: Revolver – Often seen as a contender for the band’s greatest album. After a much-needed break from constant demands, The Beatles were in full experimental flow. Song structures were becoming stranger and stranger, nowhere more so than on Tomorrow Never Knows with its thudding rhythm, backwards tape effects and total disregard for the verse-chorus approach. She Said She Said was based on an LSD trip the band took with actor Peter Fonda. Elsewhere, opening track Taxman was George Harrison’s response to the band finding themselves in the ’supertax’ bracket.

:: Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band – Probably the defining album of 1967, recorded after the band had quit touring and had begun their ’studio years’. With a lavish cover masterminded by pop artist Peter Blake, for which he was only ever paid about £200, the band had a loose concept about the titular group although this is not reflected in many of the songs. The band spent more than four months in Abbey Road working on the tracks, ranging from the touching She’s Leaving Home to Harrison’s sitar-drenched Within You Without You. The highpoint is A Day In The Life – essentially a Lennon song welded to a McCartney song with an incredible George Martin-scored orchestral build – and with one of the most famous final chords of all time.

:: Magical Mystery Tour – Originally a two-disc EP to accompany a BBC Christmas special, with just six songs, about a bus adventure with a nod to Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters; it was later expanded to an album in 1976 with added tracks from the same period which were not on albums, such as Hello Goodbye, Strawberry Fields Forever and Penny Lane. Lennon’s Lear-inspired nonsense song I Am The Walrus later became a live fixture at Oasis’s gigs.

:: The Beatles – commonly referred to as ’The White Album’ due to the plain sleeve, the album captures not only a prolific period of song-writing as the band decamped to Rishikesh, India, but also a troubled few months as tensions within the band boiled over. Ringo Starr quit for a while leaving Paul to drum on some tracks including Back In The USSR. Across a double album, it contains the broadest stylistic range of any Beatles recording including the proto-heavy metal of Helter Skelter and pastiches such as Piggies and sound collage of Revolution 9. While My Guitar Gently Weeps also broke new ground by introducing a featured soloist on to their recordings with Eric Clapton playing lead guitar.

:: Yellow Submarine – Another soundtrack, this time to the animated movie which, although nominally starring the band, was voiced by actors (including former Coronation Street actor Geoffrey Hughes). Some songs had been released before including the title track, while others such as Only A Northern Song and Hey Bulldog were heard for the first time. The album’s second side was an orchestral score composed by producer George Martin.

:: Abbey Road – The last album recorded by the band, but due to the band’s release schedule, not the last to be issued. Contains Harrison’s masterful love song Something, as well as one of the least popular Beatles songs Maxwell’s Silver Hammer. The second side contains a 16-minute medley of song fragments which were pieced together culminating with The End, which was prophetically the last song recorded by all four Beatles. The famed cover features the band walking across the zebra crossing outside the Abbey Road studios.

:: Let It Be – After the squabbles and brief departures of The White Album, The Beatles wanted to make a back-to-basics album, Get Back, where they would rehearse and record together in early 1969. But creative tensions meant the original plan was abandoned and they moved from Twickenham Studios to their own Apple studios to finish recordings. Scheduling conflicts pushed the release into 1970 and the tapes were then given to producer Phil Spector to finish. The album did not appear until May 1970, by which point the band had split. It included One After 909, a song which had been kicking around since the early 1960s, as well as two of McCartney’s most anthemic tracks Let It Be and The Long And Winding Road (although he was never happy with the over-indulgent treatment Spector gave them and erased the producer’s efforts for a new version Let It Be … Naked in 2003).

:: Past Masters – A compilation of the band’s singles (a-sides and b-sides) and alternate version which had not already been featured on albums, put together to allow fans to have an overview of almost the entire Beatles’ catalogue. The new CD version is a double album bringing together the albums which were previously released in two volumes.

Review from Consumer Reports is right on the money....

The Beatles reissues. As Beatles fans are aware, tomorrow also marks the availability of the first remasterings of the full Beatles catalog in more than 20 years—an eternity in digital time. Most reviewers raved about the improved sound of “Love,” the 2006 Beatles’ Las Vegas show (and CD), which includes remastered versions 20 Beatles songs from the team responsible for this week’s reissues.

But there are also reasons to grumble about this week’s re-releases, even before hearing them. The extras are confined to making-of video documentary on each album. Also, though the albums have been remastered in both stereo and mono (the latter being the preferred format by some Beatles fanatics), the reissues do not combine both versions on one disc—as recent reissues for many other 1960s bands have done. Rather, when bought singly, the reissues only carry the stereo version of the album. To get the mono, you must buy the entire catalog, in a box set that lists at $300—if you can even get it (it sold out in advance at many retailers, though a second run is promised). And the titles aren’t being issued in Blu-ray or DVD formats, and hence there are no 5.1-channel surround versions as of yet.

To many observers, including me, the formatting decisions look like an attempt to sell diehard fans those thirty-something-minute-long Beatles albums not just once more, but several times more over the coming years. That’s a little unseemly from a band that’s traditionally been classier than most. —Paul Reynolds.