January 24, 2025

January 22, 2025

The Beatles 1987 CDs Still Preferred By Many

A lot of people are not fans of the recent Beatles Deluxe reissues. Some claim the sound is lacking in dynamic range compared to the original recordings. The 1987 first CD issues were taken from the original master tapes and many are "flat transfers" (confirmed). You can hear the tracks in their pure form. And while most agree the 2009 remasters are much improved in bass, they also cut the dynamic range in favor of louder recordings. If you want to hear the most natural recordings, the 1987 CDs are still preferred, especially from the period Sgt. Pepper forward. Of course, everyone has their favorites. And for this reason, the 1987 CDs have a place in every Beatles collection. These CDs also provide the durable jewel cases and artwork. Grab these CDs while you can off eBay and other sources, because they are no longer available for purchase new. The Mono Masters on CD are also preferred due to their greater dynamic range. Either way you can always listen to the CDs since they no longer appear on streaming sites. So here are several articles on the topic:

The 1987 CD mixes

In 1987, as the Beatles catalog was due for their first CD release, producer George Martin wanted to go back and remix the sixties version of stereo to something a bit more updated for the modern ear. Because of a rushed release schedule, he couldn’t do this for the first four albums, Please Please Me, With The Beatles, Beatles For Sale and A Hard Day’s Night, as they were due for release in February 1987. So, as a compromise, they were released in mono, which were mixes the producer was satisfied with.

The next batch of releases were Help!, Rubber Soul and Revolver, due out in April 1987, and this time, Sir George had time to prepare updated mixes for these. He had a listen, and while he thought Help! and Rubber Soul needed remixing, he was satisfied with the sixties stereo mix of Revolver and all the albums that followed.

So he remixed Help! and Rubber Soul, and when they were released on CD they had an “eighties” stereo soundscape. (Except for some Canadian pressings of these CD’s where the original sixties stereo mixes had been used by mistake.)

Over the years, Beatles fans and music lovers have been rather critical to the 1987 mixes of those two albums, especially because they brought in an amount of echo and reverb which hadn’t been present on the sixties stereo mixes. Then, when the remasters were announced, these fans were shocked that they were once again to use these inferior 1987 remixes for the general release of the remastered catalog (albums available individually and as part of the stereo remasters boxed set).

In a telephone interview that Detroit’s Classic Rock station’s (FM 94,7) Deminski and Doyle conducted with Giles Martin, son of Sir George, the producer unexpectedly was able to shed some light on why the eighties mix was re-used.

Deminski and Doyle had made several erraneous assumptions, first of all they thought that Giles was involved in the remasters project, secondly they assumed that the remasters were also remixed, not just remastered. As these assumptions were both untrue, the interview do provide an insight into the narrow world behind the walls of Abbey Road studios and the hap-hazard manner in which things happen.

Giles Martin was in the studio, remixing the Beatles songs that were going to be used in the The Beatles:Rock Band game, singling out specific instruments from otherwise interlocked studio tapes, so he was able to talk a bit about that process.

But he was also involved in the “Love” project, and he was an insider at Abbey Road, so he was also able to listen in to the remasters project that was going on at the same time as he was mixing for RockBand. Here’s what he said (transcribed by me from the podcast of the interview) about those infamous 1987 remixes:

Giles Martin: Rubber Soul and Help! were remixed by my dad in 1988 or ’87 for CD. And when we did “Love”, we got to do Yesterday, and I couldn’t understand why there were so much echo and reverb on the voice ’cause it was very non-Beatles. And it was only when I came back and I was listening to the remasters I asked “how come this is the case?” and they said “well we are remastering the eighties versions of [Rubber Soul and Help!]” and I said “why aren’t we remastering the originals, we should remaster what came out then [in 1965]?”

And they said “Well, your father wouldn’t be very happy with us not remastering the versions he did in the eighties.”

So I spoke to my Dad and I asked “Do you mind if they remaster the sixties version?” and he went “I don’t even remember doing them in the eighties!”

Allan Rouse in an interview with Record Collector: “The remasters were based on the master-tapes, with the exception of two albums: George Martin’s 1987 mixes of Help! and Rubber Soul. People are questioning why we used those. George Martin is the fifth Beatle. He chose to do it. You can argue with him, but I’m not going to.”

So there you have it! The stereo remasters are the 1987 remixes out of the involved remastering engineers’ misguided respect for Sir George!

Now, the original 1965 stereo mixes are not lost to the world, because they are an added bonus on the mono remasters of those albums, but these are only part of the mono boxed set, and are not for sale to the general public as individual albums.

Source: https://webgrafikk.com/blog/uncategorized/1987-cd-mixes/

03-08-1987, from the New York Times

The resonance of that decision remains with us to this day, for while Beatlemania may be more subdued than it was in the 1960's, a remnant of it has remained alive through the 17 years since the group disbanded. Right now it's having one of its periodic waves of high visibility, and that has traditionally meant that there's money to be made for those with Beatles trinkets to sell. This year's hot items aren't Beatles lunchboxes, wallpaper or gum cards, but rather, increasingly high-tech ways of collecting the band's work.

Ten days ago, EMI released the first four Beatles albums on compact disk. These CD transfers have been a long time coming, but have they been worth the wait? In a general sense, yes: they put forth a crisp, powerful and beautifully detailed sound, but they're also short - less than 35 minutes each - and they're in mono. These aspects and several others leave one wondering whether the label's Beatles CD program ought to be reconsidered.

Meanwhile, there has been other Beatles activity. Two weeks ago, for instance, ''Help!'' was released on video tape (with a full stereo soundtrack), joining the already available home video versions of ''A Hard Day's Night,'' ''Magical Mystery Tour'' and ''Let It Be.'' A laser video disk of ''Help!'' featuring segments deleted from the theatrical version is forthcoming, as is ''The Making of 'A Hard Day's Night,' '' a video documentary also featuring footage previously seen only by the most obsessive collectors. Beatles cartoons are back on TV. And two documentaries marking the 20th anniversary this June of ''Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band'' are in the works.

Say what you like about Elvis Presley, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, the Police or Bruce Springsteen, no performer of the rock era has had anything like the social and cultural impact the Beatles had, nor has any pop ensemble produced so consistently brilliant, influential, varied and durable a body of work. Between their first EMI recording session, on Sept. 4, 1962, and their last, on Jan. 3, 1970, the Beatles recorded and released 211 songs, or nearly 10 hours of music.

The four new CD's, which use the cover art, liner notes, track orders and even the Parlophone logo of the British originals, are ''Please Please Me'' (CDP 7 46435), ''With the Beatles'' (CDP 7 46436), ''A Hard Day's Night'' (CDP 7 45437) and ''Beatles For Sale'' (CDP 7 46438) - a chronological sequence that takes the band's album releases through the end of 1964. According to EMI's plan, ''Help!,'' ''Rubber Soul'' and ''Revolver'' will be released in April. June will bring ''Sgt. Pepper,'' and by the end of the year, ''The Beatles (White Album),'' ''Yellow Submarine,'' ''Abbey Road'' and ''Let It Be'' will be out too. That covers the 174 tracks that were originally issued on LP. Missing, however, will be the 37 songs (plus four alternate takes) released as singles and EP tracks -in other words, most of the group's biggest hits. These, or some of them, will be issued next year in a compilation that EMI has not yet formulated.

On the four CD's just issued, the sound is magnificent - solid, crystal clear, beautifully textured and fully detailed. One hears very little in the way of tape hiss or extraneous noise; heard side by side with their equivalent mono Parlophone LP's, the CD's sound, for the most part, as bright or brighter on top, and a good deal richer in the bass.

Moreover, the domestic release of these British disks also redresses a longstanding flaw in the Beatles' American discography -the fact that until ''Sgt. Pepper'' the Beatles' American disks bore very little resemblance to those the group and George Martin carefully constructed at the Abbey Road studio in London. Typically, a run of Beatles sessions would produce about 16 tracks, two of which were issued as a single, while 14 were sequenced for the LP - the group's rather considerate philosophy being that someone who bought the single shouldn't have to pay for the same tracks on an album. Often, a second single was issued between two LP's, so that every six months or so, the Beatles would have released 16 to 18 tracks.

When these recordings were sent to Capitol, EMI's American arm, however, they were promptly dismantled and made to conform to a set of house rules. First, it was Capitol's policy that an LP contain no more than 12 selections; so two were dropped from the British album sequence right off the top. Second, it was felt that songs released as singles should appear on LP's, so more album tracks were dropped to make room for the latest of the 45's. Finally, it was decreed that American record buyers expected a brighter, hotter kind of sound than their British counterparts, so the tapes were lavishly immersed in artificial echo. So, for every three British LP's, Capitol sold the American public four shorter and sonically murkier albums.

Don’t Look Now, but Kidz Boppers Have Graduated From College

But while the CD's offer the original sequencings and sound quality, they raise other questions that bear examination. From the campaign EMI has been building around these disks, it strikes me that a number of questionable decisions were made, both in terms of the Beatles CD program on the whole, and with regard to these first disks.

For instance, the fact that these first four CD's have been issued in mono is bound to bother some collectors. In the case of ''Please Please Me'' and ''With the Beatles,'' that's certainly a defensible approach, for when they were recorded, in 1963, George Martin had only two-track equipment at his disposal. At the sessions, he recorded the instruments on one channel and the vocals on the other - an arrangement he found convenient in producing a mono mix, but awkward for stereo.

Without question, the mono mixes pack a greater punch. What the stereo versions (instruments on the left, vocals on the right) have going for them, though, is that they allow one to peer freely into the details of the arrangements - a fascinating pursuit if one's interest in the Beatles is musical rather than nostalgic.

But ''A Hard Day's Night'' and ''Beatles for Sale'' were recorded on four-track equipment, and their stereo mixes are bright, spacious and really quite lovely. Why mono CD's then? Bhaskar Menon, chairman of EMI Music Worldwide, recently explained that ''in very close discussion with George Martin, we determined that there was no question we must preserve the original mixes - that the releases really must be in mono because stereo was not the intent of the performers.''

But George Martin tells it this way: ''Expediency, in a word,'' he said. ''EMI did not consult me until December, by which time they were ready to have the disks pressed. When I heard the stereo CD's, I thought they sounded awful. I told them that the first two should go out in mono, and that if they had to issue the others in stereo, the mixes should be cleaned up and re-equalized for CD. Unfortunately, there was a deadline to be met, so they said, 'Look, we'll release all four in mono, and if you like, perhaps you can prepare stereo mixes for ''A Hard Day's Night'' and ''Beatles for Sale'' later on.' ''

Far be it from me to disparage the mono mixes. From ''Please Please Me'' through ''Yellow Submarine,'' each of the Beatles albums was simultaneously issued in both mono and stereo, and one of the great joys of Beatles collecting is that moment when you realize that, in quite a few cases, these separately prepared mixes feature either alternate vocal takes, radically different instrumental balances, or, in the later recordings, different sorts of effects. ''We tended to change our minds a lot,'' Mr. Martin explained, ''mainly because we didn't think it was that important to be consistent. Of course, history has found us out.''

In some cases, the mono mixes are clearly more interesting, particularly on the later albums. On the mono ''Sgt. Pepper,'' for instance, John Lennon's vocal in ''Lucy in the Sky'' is set in a spacey, echoic haze, perfectly appropriate for the song, but lost in the stereo mix. On the same disk, ''She's Leaving Home'' is speeded up in mono, changing the pitch, and that version doesn't drag nearly as much as the stereo one. And on the ''White Album'' (which was released in mono in England, but only in stereo here) about half the tracks boast fascinating mixing variations.

In fact, what's objectionable about EMI's campaign is not the use of the mono tapes, but the company's trumpeting of its claim that ''these are the first four British albums, in their original mono mixes'' - as if the British stereo mixes were less original. It's a murky topic, though. When the question of the original mixes was raised, EMI's London-based spokesman said, ''The first two albums were issued only in mono in 1963. It was not until 1964 or 1965 that they were remixed for stereo.''

Yet, a check of Parlophone's 1963 advertisements for these disks, when they were newly released, confirms that they were indeed issued in both stereo and mono. ''I can't understand that,'' George Martin said when this was pointed out. ''Certainly, I didn't mix them in stereo, nor did the Beatles, and I don't think I was aware that they were out in stereo at the time. Now, that may sound extraordinary to you, but in 1963, I scarcely had time to eat breakfast, let alone keep up with what EMI was releasing.'' That would account for only the first two disks. But if the main reason the others are in mono is that EMI didn't have the time to make the stereo disk properly, must the label coerce history into supporting its last-minute decision?

Having been invited, belatedly, to participate in the CD preparations, Mr. Martin is now in the process of remixing ''Help!,'' ''Rubber Soul'' and ''Revolver'' from the four-track masters. ''My intention was not to change anything,'' he explains, ''but the original mixes sounded a little woolly to me, so I was able to harden up the sound and cut down on some background noise.'' Mr. Martin says, however, that the last few disks in the series - from ''Sgt. Pepper'' onward - will probably not be remixed.

The best solution, of course, would have been to include both the stereo and mono mixes of each album on each CD, and let the listeners decide for themselves. There's lots of room: these four disks run a bit over 30 minutes apiece, and most of the pre-''Pepper'' disks are similarly brief.

Alternatively, EMI could have added, at the end of each CD, the singles and EP tracks that were issued concurrently, with a suitable addendum at the end of the program notes booklet. For that matter, while reprinting the original liner notes was a nice (and, from a collector's point of view, necessary) touch, a supplementary essay setting forth recording and release dates, and discussing the music in the context of the band's full output, should not have been too much to expect at this point.

Finally, it seems silly to stand on ceremony about the ''original 12'' British albums in every case. Is it really sensible to skip a unified compilation like ''Magical Mystery Tour'' simply because it wasn't originally issued on LP, while a CD version of ''Yellow Submarine''- an album containing one track from a previous disk, five otherwise untransferred Beatles tunes and a side of incidental film music - is imminent? Both would fit on a single (and chronologically appropriate) CD.

During the four years between the arrival of CD and the release of these disks, Beatles collectors wondered how EMI would present the Beatles on CD. Unfortunately, EMI seems to have devoted less thought to its CD program than many of the disks' prospective buyers have.

The transfers are fine, and the music is as exhilarating as ever. But as has often been the case, one gets the impression that EMI is intent on providing the minimum and feigning authenticity, largely because its executives haven't properly thought the series through. It's a pity, really, because with a little effort, EMI could have lived up to the advance fanfare for these CD's, and made the series something special. Perhaps it's not too late.

A version of this article appears in print on March 8, 1987, Section 2, Page 25 of the National edition with the headline: BEATLES ON CD: YEAH, YEAH, NAH. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/1987/03/08/arts/beatles-on-cd-yeah-yeah-nah.html

The Beatles Remasters- The Stereo Albums and The Beatles In Mono -from The Absolute Sound, by Neil Gader Sep 11, 2009

Source: https://www.theabsolutesound.com/articles/the-beatles-remasters-the-stereo-albums-and-the-beatles-in-mono/

The Beatles Remasters: A Splendid Time Is Guaranteed For Most

Michael Fremer-Dec 31, 2010How bad were the original Beatles CDs issued back in 1987? So bad that even the clueless conditioned to believe that CDs represented an automatic sonic step up from vinyl noticed something was terribly wrong.

Amusing to some observers was the nature of the complaints: “they sound tinny,” “they sound flat,” “they sound thin and bright,” “they’re harsh and edgy,” “where’s the warmth?” etc.

Why did it take The Beatles for these folks to notice how bad almost every attempt at re-mastering great analog recordings to CD sounded?

I can’t name a single CD reissue back then that sounded as good as the original LP version, never mind any that sounded better, yet the same folks who chucked their LPs and were happily munching on their crispy CDs somehow heard all of the problems with the 1987 Beatles CDs they might have heard with all of their CDs had they paid more attention.

Leave it to the mythical Beatles to pull down the CD format’s digital pants and expose its, er, shortcomings. Not surprising since the group has held a special place in the hearts, minds and souls of generations and not surprising considering how well recorded the albums were—even the “primitive” early ones, thanks to the EMI studios, engineers Norman Smith and Geoff Emerick and of course producer George Martin.

Add low rent, almost dismissive packaging for such hallowed musical ground and the curious decision to issue the first four in mono only, when both mono and stereo versions would have fit on a single disc and you have a truly shitty reissue program, one that thumbed EMI’s corporate nose at both the surviving Beatles and especially the group’s fans.

The New Remasters

As reported elsewhere on this site and all over the media, this time EMI was determined to do a much better job and by any standard they have, both in terms of the sonics and especially the packaging.

The stereo box is deluxe in every way, with gatefolded digi-pak style jackets, original label artwork, previously unseen photos and Quick-Time mini-documentaries accompanying each disc. An additional disc holds all of the documentaries so you can watch all of them without having to go through the individual discs. In addition to the original releases, the set includes a double CD of singles and EPs not appearing on the original UK sets, which usually omitted the singles.

One curious move was the decision to use George Martin’s 1987 re-mixes of Rubber Soul and Help! instead of the original stereo mixes. These were digitized at 16 bit/44.1K resolution using what today would be considered stone aged A/D converters.

So if anyone tells you that the “new” Rubber Soul and Help! reissues sound so much better than the 1987 issues, ask them what they weren’t smoking. Surely, mood enhanced they’d notice they were listening to the same mixes, only perhaps a bit louder and punchier due to the touch of compression applied to all of these stereo reissues.

Ironically, if you want to hear the original stereo mixes of Rubber Soul and Help! transferred without compression you’ll need to buy the mono box! Yes, the producers chose to tack the original stereo mixes onto the mono CDs of these two albums. More about that later.

The compression applied is so minor it’s not worth worrying about. Yes, these reissues do sound a bit “punchier” and “louder,” but overall the reissue producers have not messed around much with what was on the tapes that they transferred at 192K/24 bit resolution, with one notable exception: clearly they’ve boosted the bass on every one of these stereo masters and I don’t write that simply because I’m used to the LPs and perhaps the LPs had their bass slightly rolled off. I’ve heard the master tape of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and there’s more bass on these reissues than I remember hearing on that tape.

On a full range playback system, one that’s reasonably flat to 20Hz, the added bass, though tastefully done, can become oppressive after a while, but for most listeners both the added bottom and the “pop” provided by the compression will sound like pleasing “fresheners” instead of deal breakers. Don’t worry: these reissue do not sound like the “modernized” abomination that was 1.

What excites most listeners about the new reissues is the return of the tactile, warm sound, or some of it at least, found on the original LPs. These CDs do sound really good, with some expression of instrumental textures, depth and inner detail resolution. For folks who grew up on the ’87 CDs and who haven’t touched base with the original vinyl (or any vinyl since 1987), these CDs are a revelation.

They are as good as one can expect from CDs but surely the process of reducing 192k/24 transfers to 44.1k/16 has taken a toll on various aspects of the sound because the original UK vinyl still beats these CDs in most ways, by a narrow margin in some and by a much wider one in others.

For instance, on the cover of Buddy Holly’s “Words of Love,” there’s a particular ring to the high pitched electric guitar lines that one hears live and on the original LPs that just doesn’t register on the CD. The ring should jump out at you as it does live and on the LP. On the CD it remains boxed in physically and is tonally truncated. And yes, you can be an aging boomer whose hearing may not be what it once was, and yet still hear it.

The handclaps sound very good but they just don’t sound fleshy-real as they do on the LP, nor do they inhabit the separate space they do on the LP. Nor do the vocals project into 3D space. The harmonies, so easily split into separate voices on the LP fuse into one on the CD. John Lennon’s voice has a chilling quality that cuts through you on LP throughout the Beatles catalog. It’s lacking on the CD. You can feel Lennon alive on the other side of the mic on the LPs, you don’t derive the sensation on the CDs good as they are.

The CDs are genuinely pleasing to listen to physically and intellectually, the LPs sound even better and they take you for an emotional roller coaster ride the CDs just don’t. That’s not just my reaction: it’s what everyone who’s listened here heard, including people who don’t have an analog axe to grind.

On the other hand, the closer the digital comes to the analog—and these CDs come closer than most—the more the differences between the two formats assert themselves, for better or worse. Listening to these excellent sounding CDs with their jet black backdrops and ultra-cleanliness means that when you put the records on, while they do sound better, you just wish you could have the superior sound of one and the pristine perfection and black backdrops of the other! Previously, what was there on the CDs was so bad sounding, the black backdrops were hardly compensatory.

So, will a Blu-ray set mastered at full 192K/24 bit resolution (maybe with the bass turned down a bit too?) produce near perfection and sound superior to clean original LPs? I don’t know, nor are we likely to find out as such a release has not been announced.

LPs are supposedly coming next year and since Sean Magee and Steve Rooke, two of the engineers who worked on the project also are expert lathe operators (they’ve cut for Pure Pleasure, Warner Brothers, Steve Albini and others) and since Abbey Road has a very good sounding DMM lathe and since the full resolution files are right there, why wouldn’t they use the 192K/24 bit masters to produce the LPs? As The Doors box proved, once you’re at that resolution, it’s almost analog.

In the case of The Doors, the deteriorated tapes made a one pass digital transfer a necessity. The Beatles tapes are in excellent condition and the original tapes could be used to cut from analog but at this point in time you can be the powers that be prefer consistently across format lines to religious purity, so don’t expect AAA, though we can hope, as we can hope for fold-over laminated cover art as well done as the fold-over, laminated mini-LP CD sleeves complete with facsimiles of the original inner sleeves found in the mono box.

The Mono Masters

Given a choice of one box or the other, I’d opt for the mono box. For one thing, the transfers were apparently done without compression or augmented equalization. They are what’s on the tape, though again, the 192k/24 bit masters have been squeezed through the redbook CD sausage machine. The mono packaging is more authentic as well. The Beatles for instance, features a miniature duplicate of the laminated, double gatefold “top loader” fold-over jacket complete with black inner sleeves, individual color portraits and fold-open poster.

The “stereo’ mixes of the first two albums, with vocals on one side and instruments on the other, produced that way to allow for vocal/instrumental balance to be adjusted later, sound interesting on the stereo box, but they sound fuller and whole in mono.

A Hard Day’s Night sound better in stereo than mono in my opinion but the mono mix is fine too. I prefer Help in stereo too (the original mix found on the mono box for sure!) but not everyone agrees with that. For Sale is preferable in stereo too, but again, the mono mix offers its own pleasures.

As for Rubber Soul and Revolver the complexities of the arrangements required track bouncing. Track bouncing made a true stereo mix difficult so you a lot hard/left right stuff as on the first few albums, so overall the original mono mixes really are preferable but nostalgiacs whose genes are now encoded with the stereo mixes will probably stick with those, though the original stereo mix of Rubber Soul found on the mono box is preferable.

The mono mixes are strikingly different from the stereo ones, particularly on the later, more complex productions as anyone who has them on vinyl knows. More than just mix differences, are differing takes and parts that are highlighted in the accompanying booklet, though most of those are on the earlier albums. Some people revel in hearing and exposing these difference, like where John fluffs a lyric on one version and not the other, but that kind of thing has never excited me so you’ll have to look elsewhere for a catalogue of those.

Not many Beatles fans have heard Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band or The Beatles in mono. These are the mixes upon which the band members lavished their full attention and that will be obvious when you hear them—not that there’s anything whatsoever wrong with the stereo mixes. When I compared the original stereo Parlophone LP with the new stereo CD, it wasn’t even close: the record is richer, fuller and far more tonally pleasing. Ditto the mono LP vs the new CD.

Oh, and you also get the original stereo mixes of Rubber Soul and Help! transferred from analog at 192k/24 bit, which you don’t get in the stereo box. Needless to say those two sound much better than the remixes found on the stereo box.

The Verdict

Both the packaging and sound of these two sets (the stereo albums are available separately) are digitized editions finally worthy of The Beatles. The packaging is superb, great care went into the mastering, which attempted to bump up the sound for modern ears without ruining the ride for those used to the original sound. In that the team has mostly succeeded.

The packaging of both boxes is truly deluxe and any Beatle fan, even those who own all of the original UK vinyl, will want to have these sets for the packaging enhancements alone.

Hopefully higher resolution digital and/or analog will follow. Sure, I’d prefer new vinyl cut from the analog originals and we can all lobby for it, but I doubt it will happen.

Source: https://www.analogplanet.com/content/beatles-remasters-splendid-time-guaranteed-most-0

January 21, 2025

Remastering The Beatles 2009 Mixes- Reviews from SoundonSound & Beatleswiki

The Beatles (The Original Studio Recordings) (also known as The Beatles: Stereo Box), is a box set compilation comprising all remastered recordings by English rock band the Beatles. The set was issued on 9 September 2009, along with the remastered mono recordings and companion The Beatles in Mono and The Beatles: Rock Band video game. The remastering project for both mo no and stereo versions was led by EMI senior studio engineers Allan Rouse and Guy Massey.[1] The Stereo Box also features a DVD which contains all the short films that are on the CDs in QuickTime format.

It is the second complete box set collection of original Beatles recordings after The Beatles Box Set (1988). Two earlier album collections, The Beatles Collection (1978) and The Collection (1982) did not contain all of the Beatles recordings. Although sales were counted as 1 unit for each box set sold in the mono and stereo format, total individual sales exceeded 30 million.

The Beatles (The Original Studio Recordings) received the Grammy Award for Best Historical Album at the 53rd Grammys.[2] The box set was issued on vinyl in 2012.

Album listing

The sixteen-disc collection contains the remastered stereo versions of every album in the Beatles catalogue. The first four albums (Please Please Me, With the Beatles, A Hard Day's Night and Beatles for Sale) made their CD debut in stereo, though most songs from those albums have previously appeared on CD in stereo on various compilations. Both Help! and Rubber Soul use the remixes prepared by George Martin for the original 1987 CD releases (the original 1965 stereo mixes were released on The Beatles in Mono). Magical Mystery Tour is presented in the sequence and artwork of its original North American Capitol Records album release, as opposed to the UK six-song EP.

All CDs replicate their original album labels as first released, from the various Parlophone Records variations, to the Capitol Records label (for Magical Mystery Tour) and the UK Apple Records side A label from Yellow Submarine through Let It Be, and with the side A & side B Apple labels for discs one & two respectively for The Beatles. For Past Masters, disc one uses a mid-1960s Parlophone label design and disc two uses the (side A) Apple label design. Each of the albums except Past Masters includes a mini-documentary, mainly drawing from The Beatles Anthology (with a few animated 3D scenarios made up of original photos thrown in), about the album in QuickTime format. The Beatles and Past Masters are two-disc sets.

Please Please Me (1963)

With the Beatles (1963)

A Hard Day's Night (1964)

Beatles for Sale (1964)

Help! (1965)

Rubber Soul (1965)

Revolver (1966)

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967)

Magical Mystery Tour (1967)

The Beatles (1968)

Yellow Submarine (1969)

Abbey Road (1969)

Let It Be (1970)

Past Masters (1988)

Missing stereo session tapes

No stereo mixes exist for the 1963 single "She Loves You" and its flipside "I'll Get You" or the 1962 single "Love Me Do" and its flipside "P.S. I Love You". It was the practice at Abbey Road Studios prior to early 1963 to wipe and re-use master tapes once they had been mixed down to mono for single release.[3] For this reason there will never be true stereo mixes of "Love Me Do" or "P.S. I Love You". Although the practice had stopped by the time of the release of the "She Loves You" single, and although it is possible that the master tapes were in EMI's possession in January 1964, when the German language version was recorded, it is commonly believed that those tapes were either stolen or destroyed.[4] Competent-sounding stereo versions of "She Loves You" have been created unofficially using the backing track from "Sie Liebt Dich", but the engineers who prepared the remasters elected not to do this. Every release of these four songs has been in mono (or simulated stereo) and they appear in mono on the stereo version of Past Masters and Please Please Me. This is also the case for the single version of "Love Me Do" with Ringo on drums but at some point (fairly early on) even the mixed down mono tape of this version of the song was lost. Some authors have expressed the opinion that the original version of "Love Me Do" was intentionally destroyed in order to alleviate possible confusion between it and the more common version of the song.[5] Since 1980, new transfers sourced from reasonably clean 45rpm mono singles from private collectors have been used as the master for this version of the song.[6][7]

Two other songs in The Beatles' catalogue which also appear in mono on the stereo CDs are "Only a Northern Song" and "You Know My Name (Look Up the Number)". Neither of these songs received stereo mixes at the time they were recorded, although other songs that were similarly not mixed into stereo during The Beatles' recording lifetime were not excluded from the set: the stereo mixes of "Strawberry Fields Forever," "Penny Lane," and "Baby, You're a Rich Man" all made in 1971, the stereo mix of "Yes It Is" that was given a very limited UK release in 1986 on a mail order cassette promotion that Apple and The Beatles did not authorize[8] and was commercially released in 1988 on Past Masters; and the 2000 edit of "Day Tripper" from 1. "Only a Northern Song" was first mixed into stereo and 5.1 surround for the Yellow Submarine Songtrack album in 1999 and a differently-edited stereo mix of "You Know My Name (Look Up the Number)" appeared on Anthology 2 in 1996. "You Know My Name (Look Up the Number)" is the only track left in The Beatles' catalogue of which the original edit has never received a stereo mix despite the multi-tracks being available.

Bonus features

Included in the set is a DVD called The Mini Documentaries compiling all the short documentaries released on the individual albums in QuickTime format. The DVD features narration from all four Beatles as well as George Martin as the opening on each of the individual albums. Each documentary contains rare footage and previously unheard dialogue. There are sound excerpts from various songs, accompanied by still photos, clips of television appearances, footage from inside recording sessions, film footage from their final photo session, and material from the five Beatles films A Hard Day's Night, Help!, Magical Mystery Tour, Yellow Submarine, and Let It Be. The DVD has a red Apple label (similar to that on the original US Let It Be LP). This DVD is exclusive to the Stereo set, and is not included in the Mono version.

Limited edition USB flash drive

Apple-shaped USB flash drive

On 7 December 2009, The Beatles (The Original Studio Recordings) was also released as a limited edition of 30,000 apple-shaped USB flash drives. This event marks the first appearance for the Beatles catalogue in a high-resolution digital format being encoded in 44.1 kHz/24-bit FLAC format. CD-standard is 44.1 kHz/16-bit. The 16 GB flash drive also includes 320 kbps MP3 copies of the albums, a specially designed Flash interface, and all the visual elements from the boxed set — the mini-documentary films, original UK album art, rare photos and expanded liner notes.[9]

Although it received positive reviews from critics and users, many complaints were received [10] that the "stem" on the USB flash drive is very fragile that it can break off when attempting to remove the USB drive out of the apple-shaped holder, making the USB drive difficult to remove.

Vinyl

On 12 November 2012, the set was released on 180-gram vinyl, specially prepared for vinyl, with a 252-page book included. Also included are the inserts which were included in the original LPs such as the cardboard cutout sheet included in Sgt. Pepper plus the photos and poster included in The Beatles.[11]

Chart performance

Professional ratingsReview scores

Source Rating

AllMusic 5/5 stars[12]

The Austin Chronicle 4/5 stars[13]

Entertainment Weekly A[14]

Pitchfork Media 10/10[16]

Rolling Stone 5/5 stars[15]

Spectrum Culture 5/5 stars[17]

On the United States Billboard Top 200 albums chart the set debuted at number 15. On the Japanese Oricon weekly album charts, it debuted at number 6, selling over 35,000 copies in its first week.[18] The set was certified triple platinum by the RIAA in April 2010. The set was also certified Diamond in Canada in March 2010.[19]

In Germany, the box set reached number 37.[20]

---------------------

Remastering The Beatles

Guy Massey, Paul Hicks & Steve Rooke

https://www.soundonsound.com/techniques/remastering-beatles, 10-2009

Remastering projects don't come much bigger than this: a team of engineers spent four years in Abbey Road creating the definitive Beatles collection.

"Today's stuff has no dynamics at all,” says mastering engineer Steve Rooke. "It's really squashed, and if the Beatles were recording today I'm sure they'd be squashing their music. But we've all lived with the sound and the dynamics we've got. We didn't want to destroy that at all, but it's got to appeal to today's CD‑buying public.”

The remastering team readjust to daylight after their four‑year incarceration in Abbey Road Studios. From left (back): Simon Gibson, Sean Magee, Allan Rouse; (front) Guy Massey, Paul Hicks, Sam Okell and Steve Rooke.

The question of whether or not to apply limiting was just one of many dilemmas that faced the Abbey Road team — headed by Allan Rouse, and including Rooke and engineers Guy Massey, Paul Hicks, Sean Magee and Sam Okell — who worked for four years to create the definitive digital versions of the world's most important pop music catalogue. "We know it's going to be put under the microscope,” admits Guy Massey, "but you can't think about it in those terms, because you'd never get anything done. You'd be like 'The people who talk about this sort of thing, are they going to like this? Maybe we shouldn't do it.'”

Faced with, on one hand, the demands of purists, and on the other, the expectations of modern listeners, the team chose to take two directions at once. For collectors and audiophiles, they created a box set comprising all the original mono versions of the Beatles' albums (less Abbey Road, which was not issued in mono, and Yellow Submarine, where the original mono was a straight fold‑down from the stereo), which for the most part was as faithful as possible to the source. Simultaneously, they reworked the stereo catalogue for release in a second box set, and also as individual albums — again treating the material with respect, but not shying away from the application of modern technology, if it was felt that fidelity could be improved.

Here, There And Everywhere

So why the need for remastering in the first place? Well, for one thing, the existing Beatles catalogue on CD was incomplete. When the albums were first made available digitally, George Martin took the decision to use the mono versions of the first four albums, and the stereo versions of the rest — even though, as Guy says, "The mono was always The Mix. On Pepper they spent three weeks mixing that, and the stereo was done in three days.”

Steve Rooke's mastering room at Abbey Road.

"I found it quite fascinating,” says Paul Hicks, "because I wasn't that familiar with all the monos, and it is interesting listening to how different the crossfade is from 'Sergeant Pepper Reprise' to 'A Day In The Life' — that's very different from the mono to the stereo versions — and on 'Lucy In The Sky', the mono's got loads of phasing all the way through the verse vocals that the stereo doesn't. It's fascinating, what is now considered to be the masters and what in the '60s was considered to be the masters, and the differences.”

The Beatles' masters were originally recorded using the EMI 'British Tape Recorder' (top); after extensive tests, a Studer machine (bottom) was chosen for the digital transfers.

The Beatles' masters were originally recorded using the EMI 'British Tape Recorder' (top); after extensive tests, a Studer machine (bottom) was chosen for the digital transfers.What's more, as Paul explains, "When the CDs were released in the '80s, George Martin decided he wanted to remix Help! and Rubber Soul. So basically, the CDs that everyone knows of those two albums are actually new mixes that were done in the '80s by Geoff Emerick and George Martin.” (The original stereo mixes of these two albums are included in the mono box set.)

There's also the issue of audio quality. The catalogue was first digitised in 1986, and although it was done well by the standards of the time, the improvement in digital audio since then has been vast. "People slag off the original CDs, and I definitely think what we've got is a step up, but I don't think they sound awful,” says Guy Massey. He believes that the '80s team did apply some digital noise‑reduction, to the original CDs' detriment, but credits the improvement in sound above all to the new transfer from the original tapes: "We always had the original CDs in a [Pro Tools] Session and I'd always refer to that. Immediately, they were better.”

Studer tape machine was used to remaster The Beatles recordings.

"I think one thing people will notice is more low end and more top end, and the majority of it was what we got out of the tape,” adds Paul.

From Me To You

The transfer process was certainly treated with the utmost care. "We had a good few weeks of basically checking things like the tape machines,” says Paul. "Obviously, somewhere like Abbey Road has got a lot of different test tapes from over the years. The main thing was we didn't rush this! We experimented with different machines. We tried some with valve preamps and things, but we didn't let any of that bias us. We ended up going with the Studer A80 — we just used our ears.”

One machine that never entered into the equation was EMI's own 'British Tape Recorder', which would have recorded the masters in the first place. "They have some in storage in Hayes somewhere, but they're not in working order,” says Guy. "They would have been pretty hard to get back into the scratch they would have been in in the late '60s.”

Because of their importance, the analogue masters had been scrupulously maintained and archived. "All the Beatles tapes are in fantastic order, the multitracks as well as the quarter‑inches,” enthuses Paul. "Guy and I have been doing Beatles stuff for about 15 years, on and off, and we've never baked a Beatles tape. The formula on that EMI tape was just fantastic. The only thing we did find, which we had to be incredibly careful with when we were transferring it — and especially with the monos, which hadn't been played in 40 years — was that a lot of the glue had dried up on the edits. So on the first wind‑back you had to be incredibly careful, because a lot of the edits just split apart when winding. We had to get the gloves on!”

"For the transfer and archiving part of the process, we did it song by song,” continues Guy. "So if the tapes had come apart when we were spooling back, we'd replace all those [splices] — same length, we'd measure them all and make sure it was all pukka — and then song by song we'd transfer them. We'd transfer the first one, go back, clean the whole tape path again. Beginning of each week, we'd de‑mag the heads. We had a speed reader on the capstan all the time so we knew it was running at the right speed.”

"We'd line up and then we'd always play through, manually checking the azimuth,” says Paul. "It was amazing just by tweaking that, if nothing else, how much more top end you could potentially get. That was a significant part of the transfer process.”

George Harrison puts his feet up during a long mixing session at Abbey Road; Ringo Starr looks on.

Fixing A Hole

The digital files were recorded in Pro Tools at 24‑bit, 192kHz through a Prism A‑D converter. "The Pro Tools system was treated as a tape machine,” says Paul.

Guy takes up the story: "There was a listening period once we'd transferred an album and were happy with the transfers. We would have detailed lyric sheets and timing sheets, and between us all, we'd identify areas that we thought we would want to remove — clicks, de‑popping, if we could do it. We've got the luxury of going back to the multitracks and saying 'Is that an electrical noise? Yes it is, let's take it out.' In 'Kansas City' [from Beatles For Sale], the stereo version, there's quite a big drop-out that's very noticeable. We used Retouch in the CEDAR world to fix issues like that. And then we'd cut those fixed portions into the master file, so it wasn't a complete process we were doing there. On some tracks there were quite a few little edits we had to do.”

De‑noising, meanwhile, was confined to gaps and fades. "Until there's a de‑noising system that works properly and doesn't take the air and all that stuff that de‑noising takes off, we didn't want to use it,” insists Guy. "We'd use it in gaps. If there's no programme, just tape hiss, we would use it very subtly. It's less than one percent of the whole thing.”

The amount of restoration that could be done was, of course, limited by the fact that they were working only with the master recordings — even though, in some cases, it would theoretically have been possible to go back to the multitracks for a cleaner fix. "If there's some low‑end stuff under a vocal wind pop, or something, we wouldn't be able to achieve as great a reduction as if the vocal was by itself in the right‑hand channel,” admits Guy. "People have asked us whether we could slot in a bit [from the multitrack], but it was like 'No, we're dealing with the master mixes. That's what they did then. That's what we're presenting.'”

"This is a remaster project,” agrees Paul. "It's basically taking what George Martin, Norman Smith and Geoff Emerick considered to be the masters and making them sound as good as possible.”

Even then, the very idea of issuing the earliest Beatles albums in stereo blurs the boundary between remix and remaster. These were recorded on two‑track, but mono dominated the market at the time. "The stereos are theoretically multitracks, because it was the predecessor of the four‑tracks,” explains Paul. "You've got the band on the left and the vocals on the other side. The purpose of them being done like that was so they could then balance the mono in more detail.”

In theory, then, it would have been possible to re‑balance the vocals against the instruments, but as Guy explains, they were careful to preserve the levels as they made it to the mono originals. "Obviously, if we decided that we'd like a little bit more guitar within the balance that they'd had for the band, if that then increased the left channel a fair amount we'd rebalance the vocal to that; or similarly, if we wanted to EQ a bit of vocal out, if that upset the balance in any way we'd do a bit of jiggery‑pokery in that sense, but we didn't remix it. If we upset the balance in any way because we were EQ'ing quite narrowly, we'd always mono it and make sure we hadn't destroyed the balance.”

Getting Better

After the transfers and restoration were complete, the actual mastering began, with Guy and Steve tackling the bulk of the work on the stereo albums, while Paul and Abbey Road's Sean Magee handled the mono set. Steve Rooke takes up the story: "Guy and Paul came up to my room, we had a listen through to what was now the cleaned‑up master version, and decided how we were going to tackle each track. We took each track in turn and tried to get the best out of it sound‑wise. We were always careful not to go too far, because we were dealing with the Beatles, and everyone knows the Beatles sound, but we wanted to give the public the best possible sound we could. So we were trying to get as much separation between the instruments, as much clarity as possible. If we could put a bit more bass line or kick drum in and give it a bit more punch, we would do. So we listened to each track in turn, once we were happy with the sound, we'd put it onto my workstation. It took about a day to do 14 tracks, something like that.”

The fruits of the project are collected in two box sets. The Beatles In Mono is a faithful reproduction of all the original mono mixes, while the stereo set has been remastered with modern tastes in mind. Apart from surgical tweaks, which were done using a Prism digital EQ, equalisation was done using an almost period‑correct piece of Abbey Road history: "We came through an original EMI TG desk, which dates back to about 1972,” explains Steve Rooke. "We went through that, and once it was all in the workstation we would then compile it in the running order we wanted, gap it, and whatever, limit it and then capture it to CD.”

"A lot of the stuff we transferred flat and left, because there's no point fixing stuff that's perfect,” adds Guy. "A hundred of the tracks, maybe, we did tiny amounts of EQ'ing if we felt something was lacking in the mix. A lot of it was very subtle.”

What, then, of the controversial limiting applied to the stereo albums, which yielded a level increase of 3‑4dB? "On this we used a Junger D01, which we felt suited the sound we were after,” says Steve. "We've got several limters in the room. They've all got different sound and different effects, but this seemed to be the flattest, if you like. We didn't want the limiter to change any of the sound we'd got, and used it very discreetly.”

Remastering The Beatles

"When we did the limiting, we would then level‑correct that with the original capture and listen for any artifacts, make sure there was no pumping or anything odd happening,” explains Guy. "We purely used that as a level gain stage, as it were. So the loudest song's loudest part would be limiting a little bit, but the rest of it would just be level correction.”

Extensive reference was made not only to the original CDs, but also to the vinyl albums — which, in some cases, represent the definitive versions as far as listeners are concerned. These had been cut at Abbey Road, meaning that the team had access to the original cutting notes as well as the resulting discs. "It's very interesting to see what was done,” says Guy. "Quite often, not that much. They had to filter quite a bit of the low end off to get it on and cut a loud vinyl, and then obviously add top towards the centre [to compensate for so‑called 'diameter loss'].”

Yet another debate in which purism and modern tastes clash is over the question of gaps between songs. "In the '60s, there was a set rule that when they were banding an album together, it was six seconds per song, which obviously is incredibly long by today's standards,” says Paul. "So on the monos we did decide to keep it exactly as it was, but on the stereos we got a bit more creative.”

"Even on the '80s CDs we felt some of them were a bit long,” says Guy. "Some of them were maybe a bit short. So we did them on a more musical basis.”

The remasters were revised several times as a result of further listening, before test CDs were sent to the band's Apple HQ for approval. Such was the surviving Beatles' faith in the team that they had allowed the project to run to completion with no intervention at all. "Basically, Apple told us to get on with it!” says Paul. "We did it, and when we were happy we sent discs out to Apple, which went out to the shareholders — ie. Paul [McCartney] and Ringo [Starr], Yoko [Ono] and Olivia [Harrison].”

"And the phone didn't ring,” says Guy, with obvious relief. He pauses for a second. "Yet!”

===============

De‑mixing The Beatles: Rock Band

Few were surprised that the Apple Corporation had decided to revamp the Beatles catalogue for the iTunes age, but the announcement of a special Beatles‑branded edition of the Rock Band video game raised plenty of eyebrows. "Dani Harrison, George's son, was a fan of the game,” says Paul Hicks. "I think he got to know one of the members of the team who make Rock Band, and one thing led to another, and it ended up going to Apple, and everyone thought it would be a good idea to do it. I think more and more people are realising that it's a legitimate outlet for music.”

You can play as any of the four Beatles, and the playing principle requires that their individual instruments be streamed on separate tracks — something of a challenge when, in many cases, they were all recorded to one! Paul worked with Giles Martin to prepare the music for the game. "A lot of people have said, 'Do you just put the stereo mixes in?' Well, no, because if you stop playing the guitar, the guitar has to stop playing. If you stop playing the drums, the drums have to stop playing.

"There's guitar, drums, bass, vocals and, on this game, backing vocals as well, and there's a backing track which is everything else, so maybe strings or something. We did push the boundaries with that sometimes — if there isn't a guitar for three‑quarters of a song, we'd put a string element in or a piano element in, so at least the guitar can still be playing something.

"We start with the multitrack. We basically mix it, we get happy with the sound of it — we've still got the plates and everything here — you make it sound like the mix and then you have to 'de‑mix' it. Every era has its own challenge. When you get to the end [ie. the Abbey Road album] it's a little easier because everything went to 8‑track. Again, Giles and I went through a lot of thought processes, and we ended up utilising Simon [Gibson] here with his Retouch system. With a lot of the processes we'd been fiddling round with on the remasters, it was like 'Maybe we can push it further and try some advanced filtering.' And a lot of the time we'd get it back and Giles and I would look at each other and be like 'Bloody hell, that's brilliant.' We'd be taking the bass line out and this and that — it's one of those things that you don't know until you try it — but obviously, if you just filter the low end out, you're going to be getting rid of the kick drums and stuff, which we weren't comfortable doing. We knew there would be limitations, because a lot of the time you've got drums, bass and guitar all on one track, so you have to look at it as an advanced bottom/middle/top instance.

"Once we were happy with that, it would go off to Harmonix‑MTV Games. They would encode it and we would get it back and play it, and Giles and I would sit down and think 'Maybe for the sake of the game...' We did a few little tweaks, like 'You can't quite hear that guitar.' And for some of the live ones we brought things in a tiny bit.”

Source: https://www.soundonsound.com/techniques/remastering-beatles

Review: Beatles Mono and Stereo Remasters Box Sets

SO, HOW DO THEY SOUND?

THE HOWS AND WHYS OF THE 2009 REMASTERED MONO AND STEREO BEATLES CATALOG,James N. Perlman

Introduction

On September 9, 2009, EMI/Capitol released the entire Beatles catalog, both stereo and mono, in a remastered CD format. The primary purpose of this essay is to discuss the remasters largely in terms of their sound. Listening occurred on what would be considered an audiophile system with Quad 988's and a Rel sub-bass as the speaker system. The conclusion I reach, after listening to both the mono and stereo remasters, is that, overall, the mono remasters are the better, truer, releases, not only in terms of content, but as also in terms of pleasure, and trueness, of the listening experience. [The mono mixes were the ones the Beatles and George Martin worked toward through The Beatles (The White Album).]

Universal Observations About the Sound of All of the Remasters

Before I address the primary subject of this article I want to address the first question many people ask when it comes to these remasters: Why remasters instead of remixes and remasters, as has been done with other catalogs from other musicians and groups from this era? When we think about the process of getting Beatles material into commerce, it seem pretty logical that remasters are probably the way it had to be in order to get these albums out. Sometimes we forget that in order for this enterprise, or most any Beatles enterprise, to get off the ground Paul, Ringo, Yoko and the Harrison estate have to come to an agreement. It is one thing to start a new project, like Love, and do a remix. It is quite another thing to start down the path of a remix of the core, legendary, catalog. A deal breaker could be just as simple as someone complaining that in a proposed remix someone else had been mixed louder than in the originals. That would end the discussion. For this reason, we will always be "stuck" with remasterings, or re-issues on advanced formats, rather than any form of remix. It is also the reason why EMI really didn't involve any of the Beatles in this project. Instead, when the project was finished, EMI presented the finished products to the Paul, Ringo, Yoko and Olivia Harrison and they were simply asked for a thumbs up or down. (Stereophile, October, 2009, Vol. 32, No. 10, p. 117)

Once it is realized a remix just couldn't be in the cards (thereby really improving the sound, as we heard in Love and Let It Be Naked), the remastering team was confronted with the original master tapes. Now, another problem crops up: the quality of the sound of the original recordings. Most people understand that from a technical perspective, at best, these were only OK recordings for the time. No one claims these were great recordings [save perhaps for Abbey Road and possibly The Beatles (The White Album)]. The reasons the bulk of the catalog can't be considered "great" recordings are because of the technical limitations at Abbey Road Studios I discuss later in the individual review of the album A Hard Day's Night. The reality of the matter is the Beatles mono recordings do not even compare favorably with earlier American mono recordings, such as Buddy Holly or, going back even further, Little Willie John. Similarly, overall, British stereo recordings from this era tend to lag behind American stereo recordings. Consequently, the remastering team was confronted with two very significant inhibitors in terms of making these re-issues sound great: 1) they couldn't re-mix the albums and 2) the actual sonic quality of the source material. The aforementioned Stereophile article also provides additional technical information regarding the remastering process that is pertinent to my conclusions about how these remasters sound:

- Tape Recorder used: Studer 80.

- Compression/limiting: Yes on the Stereos but "gingerly" according to Allen Rouse. Specifically, according to Rouse, the average level of the mixes was raised 3-4 dB "to make better use of the CD's dynamic window." Stereophile, November, 2009, Vol. 32, No. 11, p. 3. Limiting was not performed on the monos. When asked why limiting was used on the stereo remasters, Rouse replied: "When everybody stops limiting, then I guess that's probably the best thing that can happen, but everybody wants theirs louder... Everybody had phasing; it was a fashion, and then eventually people grow up and work out how far and how much you should use these things." Rouse stated they did not want to compromise the dynamics. But, as the graphic below seem to indicate, dynamics were affected.

- Pro Tools: Yes at 24 bits/192 via Prism A/D converter.

- NoNOISE Yes but only for a total of 5 of 525 minutes. Read more about Sonic Solutions NoNOISE (PDF).

Point No. 2 from the Stereophile article provides a launching point for one reason I find the mono remasters more satisfying than the stereo remasters.

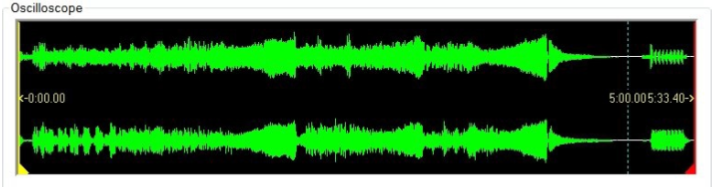

If one takes a very simply oscilloscope, found in any commercially available CD burning software, it is clear very little was done to the mono remasters, just as Rouse stated. Here is a graphic of the song "A Hard Day's Night" taken from the 1987 mono re-issue:

Now let's look at the same track from the 2009 mono re-issue:

There is slightly less headroom in the 2009 remaster, and the track starts with a tad more gain. But, if anything, the 2009 mono actually shows a bit more definition in the dynamics without any clipping. On paper, this appears to be a good thing and a good job.

Regrettably the same cannot be said for the stereo remasters. As written above, compression/limiting was used on the stereo remasters. Compression changes the sound and wave form. It can make things sound uniformly, or more uniformly, loud. It can make a recording fatiguing and/or harsh. Dynamics at the peak of sound are almost always affected. Read more about compression...; Read more about the "loudness war"...

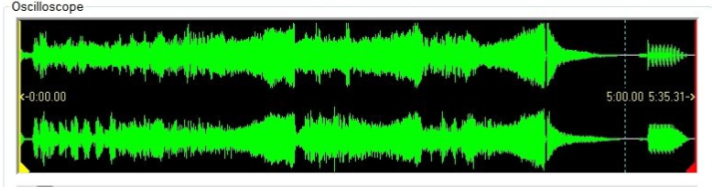

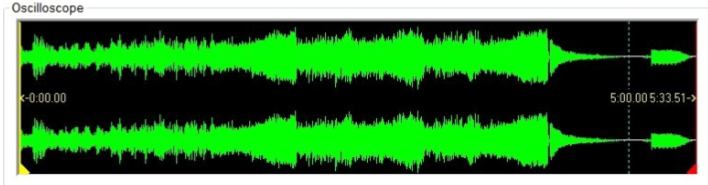

Again, the use of a simple oscilloscope reveals how this manifest itself in the 2009 stereo remasters. First, here's a graphic of "A Day In The Life" from the 1987 CD:

Now here's a graphic of the same song from the 2009 remaster:

Now look very closely at the graphs. In a few spots you can actually see where the tops of the volume are cut off by the compression in the 2009 stereo. One place is at the end of the song before the final piano chord. Notice how on the top channel the piano chord is as loud as the preceding orchestration as it reached its peak. Yet, in the 1987 graphic, you can see how the end of the orchestration is actually louder than the piano chord. Any question of regarding the relative actual loudness of the orchestration versus the piano chord is resolved by looking at the graphic of the 2009 mono:

Our ears can play tricks on us. Oscilloscope, not so much. Let's be clear about this: perhaps the most important moment in the entire Beatles catalog has been altered.

Another place is about 1/2 of the way into the song on the top channel. A third revealing part of the two graphics is near the beginning, after the crowd noise from "Pepper's Reprise" dies down. Look at the relative bloom in sound, on both channels, when the 2009 graphic is compared with the 1987 graphic. While this bloom is most apparent at the beginning of the song, it continues on throughout. This bloom is separate from the fact the song starts out with slightly greater initial gain in the 2009 remaster. A further example of this bloom can be found by comparing the decay of the piano chord in the 1987 and 2009 graphics. Again, notice the bloom in the 2009 remaster. A final revealing portion is the funky "Answer me never" found at the end of the LP. All these artifacts are functions of the compression applied to the stereo remasters.

Hence, there should be no mistake about this, the stereo remasters have changed the music. One can argue whether this results in a better sound, but most would argue it doesn't. What cannot be contended is that this is the "same" music from the standpoint of dynamics of the recordings. These graphics, and you can find many, many other examples in the 2009 remasters if you look, explains to me why, overall, I find the stereo remasters lacking. I can hear the artifacts that are prevalent in a compressed recording. This affects the "musicality" of the recording. And, at the end of the day, what counts most to me is the "musicality" of the recording.

All this provides objective evidence for the conclusion the stereo remasters are lacking. But there is an addition reason the monos, overall, sound better. This reason flows from the actual recording process. It has been said, many times: the Beatles and George Martin spent most of the time working on the mono mixes. While emphasis has been placed on the notion the monos are the definitive mixes in terms of content, and in a purist sense they are, there is another, less obvious reason, the monos sound more musical. This reason has to do with the actual recording process. Remember, each track recorded (track used in the context of this and the following paragraph means track on a tape, not the full song; as in track on an album), that was later used in both the mono and stereo mixes, was designed to fit in with the overall sound of the mono mix of each song. Thus, at the end of the mix of the monos what exists is the full musical puzzle; with all the pieces in their proper place relative to the other. This results in the intended musical puzzle fully assembled.

When George Martin went to do the stereo mixes, he took many of the individual tracks, pieces of the puzzle, that were designed to fit into the final full mono puzzle, and separated them from the whole. Consequently, while, in almost every instance, these separate pieces of the puzzle sound clearer and more distinct in the stereo mixes (and this has its advantages when one actually wants to examine individual piece of the puzzle; say a Paul bass line or a John's harmony), many times the individual pieces of the puzzle sound out of context or thin or harsh, etc. in the stereo mix. This may not have sounded so wrong to many of us, particularly to those of us living in the United States, as all we really knew were the stereo mixes. But now, as many of us are hearing this complete catalog of music in the mono format for the first time, we can now actually hear the full musical puzzle as it was intended, with all the pieces of the musical puzzle properly assembled. For this reason, it really shouldn't come as much of a surprise that many are coming to the same conclusion: the monos, overall, sound more musical and, overall, provide the more satisfying listening experience. The reason for this is simple, the monos sound more musical because the intent behind each track was that it be used to assemble a mono mix, not a stereo mix. Sure, the vast majority of these same individual tracks were later used for the stereo mixes. And sure, they will sound individually clearer (Because they are, in varying degrees, separated from the sound as a whole.). But this doesn't change the controlling point, that from a production perspective, a musicality perspective, it obviously makes a world of difference that these tracks were recorded to fit in a mono mix not a stereo mix.

While there are many songs from which to choose to illustrate this point, let's examine one song, "Can't Buy Me Love," brought to my attention by Steve Brauner and K. Giorlando. In the '09 mono Ringo's drums drive the song. Ringo's drums give the song its energy. The volume is right up there with Paul's lead vocal. However, when you go to both the '09 stereo mix and a mid-70's vinyl stereo mix, where Ringo's drums come out of one speaker, they are muted and, consequently, there is a loss of energy to both of these stereo mixes. I think it is fair to conclude that when it came to the stereo mixes, George Martin, for production/sonic reasons, had to dial back the drums when he put them on one side of the mix. Still, the musicality and, arguably, the pleasure of the song is compromised by what Martin, no doubt, had to do in order to create a stereo mix. Obviously, there are any number of songs in this catalog where the same sort of analysis could be made.

All this said, I acknowledge that musicality is only part of the calculus, albeit a very large part. Clarity, tonality, dynamics, the ability to hear separate sounds, all play a role in creating the full listening experience. Thus, as will become evident in the individual reviews that follow, the heightened clarity of a stereo mix can overtake the mono mix, when the musicality is not compromised, or not, overall, compromised significantly (A Hard Day's Night, Beatles For Sale) or when the material cries out for stereo and the stereo mixes musicality isn't significantly harmed (Magical Mystery Tour) as opposed to when the musicality is significantly harmed by the nature of the stereo mix (Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band). There are even instances where the compression applied provides a benefit. This is most prominent in the pre-Rubber Soul stereo remasters where the compression adds a bit of needed body to the tracks. This compression is somewhat similar to what Capitol did with the early releases here in the United States when Capitol enhanced the tracks with reverb and the like.

Still, in the end, I cannot come to the conclusion the stereo remasters are the definitive/best available stereo renderings. Instead, my recommendation is that people interested in the best stereo experience should stick with, or go to, either early EMI pressings or the Mobile Fidelity pressings. There are also some early 21st Century Japanese pressings, released at the same time as Let It Be Naked, which sound quite nice and quiet. As for the mono remasters, as I only have one Beatles mono on vinyl, Sgt. Pepper's, in a Japanese mid-1980's pressing, the only thing I can say is the two sound very, very, similar. As Pepper's seems to be the most challenging recording in the Beatles's catalog, this augers well for a conclusion the entire remastered mono project will compare favorably with mono vinyl pressings. Now that my general impressions of the sound quality of the stereo and mono remasters is complete, attention can be placed on the individual albums.

The Individual Albums

Please Please Me

The sound on the mono is just amazing. You can really hear the fullness of the echo as John sings Anna. The vocals just soar. Ringo was just so good, even at this early stage and so was Paul. They supported and framed the songs so perfectly. While the mono is the winner, the stereo has things to recommend. There is a bit more clarity, but this comes at the expense of fullness. If one is not bothered by the left right separation found in this, and With The Beatles, the stereos provide a complementary listening experience. With The Beatles: As with Please Please Me, the mono sounds so, so, nice. The stereo is perhaps not quite as good PPM, but the same overall comments above about the stereo PPM apply.

A Hard Day's Night

Because of the way HDN was initially rolled out here in the states, soundtrack not the EMI version, I think HDN is a bit of an overlooked album by the group. The album seems better and more enjoyable in stereo as you do get the clarity, without some of the negative sonic artifacts I find troubling on Pepper's, etc. I think the reason is that they now had four tracks so George Martin could do proper stereo mixes and still have a mostly fresh first-generation sound. Remember, there were only two track available for Please Please Me. However, when they got to Rubber Soul and Revolver, four tracks weren't enough, which required, in some instances, numerous dubs of the four tracks to another four track tape, merging the four tracks to one track, thereby opening up three new tracks. While this degraded the sound somewhat it also made it difficult to back-track and do the after-thought stereo mixes, which is why we have the atrocious "stereo" of Rubber Soul and Revolver. Consequently, the reason the monos of these albums provide the better listening experience has mostly to do with technical limitations. While the mixes on A Hard Day's Night are stereo mixes, they carry George Martin's idiosyncratic, but really right, decision to put the vocals in the center, the rhythm section to the left and the other instruments to the right. I always have loved how Martin took care to isolate the brilliant work of Ringo and Paul so many times instead of just following the convention of placing the drums in the center. This is why one of Martin's memoirs is entitled: All You Need Is Ears.

All this said, if you really want to hear HDN in stereo, and it isn't too expensive, try to find an early EMI vinyl pressing (anything from the mid-'70's back.). But for the vast majority of listeners, the remastered HDN and Beatles For Sale too, will provide immense pleasure.

Beatles For Sale

Comments, preference and reasons for preference similar to A Hard Day's Night.

Help

Thank God we have three different versions to compare to make life ever so easy. First, mono is the definitive mix, that's a plus. As a minus, while it sounds richer, it is also a bit cluttered compared with the stereo mixes. As for the stereo mixes, the remaster of George Martin's '87 remix does show some limiting in this new incarnation. A bit a hard to dial in the right volume. Sounds fuller, but that's the limiting. I am not sure I care for this version too much. As for the `65 stereo version, that comes on the same disc as the mono version, as this album is somewhat acoustic, the absence of the limiting that was done to the new stereo remix/remaster is a plus. The delicacy is there in "I Need You." Overall, the "old" stereo is prettier than the "new" stereo. One can argue over whether the "new" stereo or the ""old" stereo is better, I come down on the side of the "old" stereo, I like pretty. But as you get both the mono and the "old" stereo on the single mono disc, the cheapskate in me screams if you had a pistol to your head and only had to purchase one version of Help, it would be the "mono" disc.

Rubber Soul

Mono over stereo, if for no other reason than the left/right channel mix that plagued Please, Please Me, With The Beatles and is most egregious in Revolver.

Revolver

There is a section of "I Want To Tell You" where Ringo is so muscular and explosive in the mono that is missing in stereo and this is before we get to the issue of the left/right "stereo" of the stereo mix. Plus, there is just this overall richness of sound to the mono that is missing in the stereo. That said, it is a bit cooler to hear "Tomorrow Never Knows" in stereo. But, overall, mono, particularly considering there are parts of Revolver in stereo that sound a bit harsh.

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

The things you have heard are correct about the mono mix, the clarity and control over the notes, instruments and vocals are all there. Overall, it just sounds better, fuller and richer than the stereo 2009 CD, plus it is what the boys intended. Oddly, the thing that was most breathtaking was "She's Leaving Home;" just a full, gorgeous, sound. In stereo, it just sounds relatively wrong; thin compared with the mono. That said, because "Day In The Life" is such a mind-f the stereo is the definitive version of this song.

As I live in Chicago, and have access to one of the country's remaining great stereo stores, that also boast three incredibly knowledgeable owners and an original Sgt. Pepper's British stereo pressing, following posting this review I went over there to compare the original vinyl with the two new CD re-issues. We listened to the reference system, Naim Audio electronic and Quad speakers. There was total agreement on what we heard. First, Pepper's mono CD had better tonal balance than Pepper's stereo CD. Pepper's stereo CD had better clarity than the mono, but this was defeated by the harshness of the sound (more on harshness shortly). Thus, overall, between the two CD's we preferred the mono CD. All that said, the original stereo British vinyl pressing crushed both. It had both tonal correctness, coloration and stereo effect.

Now as to the harshness issue, please be mindful that I have listened to these discs on two audiophile systems. Something like harshness is likely to be more prevalent the higher up you get in the stereo food chain. Thus, someone who doesn't have an audiophile system may not experience the harshness at all, but it is really there. This may render some of the stereo CDs more listenable for these people than they were for me, at least when it comes to Pepper's.

Magical Mystery Tour

While Pepper's sounded better in Mono, MMT sounds better in stereo, and remember good vinyl will be better in stereo.

The Beatles (The White Album)

Both versions have their merits, you need both. If you can only go for one, it's the stereo. But remember, good vinyl will be better in stereo.

Abbey Road

The defining moment of these re-issues, and why it took four years, may be found on AR's "I Want You (She's So Heavy)." Because they couldn't take the tape hiss out without compromising the sound, they didn't. But when it came to John's final "yeah" which was over saturated and clipped previously, they were able to take the clipping out, and for the first time, you can hear all of John's vocal. With all that said, remember, good vinyl will be better, and the flat-out best sounding CD is the unauthorized Japanese issue available from 1983-1985 (Sony CP35-3016) which is quite pricey due to its unavailability and high-quality. For more information on this issue see these two helpful links: MopTop.org Review on Ebay

Let It Be